ON PERFECTION AND FLAWS IN ART AND CRAFT

In search of the Perfect Pizza.

It is in my nature to be a perfectionist. Ironically, that has only made me more aware of the flaws in my work and in my life. What I learned from the craft of cabinetmaking is flaws are at times unavoidable, so the more important thing is to know how to deal with them. If you can correct your mistake, I was taught there is really no lasting fault – therefore always pay attention and avoid those you can’t correct. However, so much depends on the tools with which you have to work. If I’d had a truly well set up shop with all the grand machines that help one quickly get the best result possible, the scale would have been a bit different than when using what I had at my disposal – constrained to non-professional, even defective tools, often having to do things by hand. The craft I learned was how to nonetheless still get a good result in spite of these deficiencies.

Over time I came to see that this was less of a handicap than it seemed. When one does something by hand, for example cutting dovetails using a simple saw, chisel and mallet, the result is governed by your hand – every momentary angle you hold the saw, how deep you happen to scribe your chisel line, even your mood at the time, since if you are impatient you can easily slip here or there. A professional can see these sometimes tiny flaws, which is the basis for any craft. Sometimes seeing them actually makes you recognize that it was handmade.

However, something very subtle may emerge out of doing something by hand that takes you out of the craft scale of having done something well or not. There is added a personal, almost organic element to what might otherwise be looked at as a thing, lifeless in itself. Much of the cabinetmaking I have done is not fancy, high end stuff, but practical, functional things needed using the cheapest materials possible. Still, even with work like that, I’ve found that people can often sense this personal character in a table, tiled floor, and so on, even if they have no conception of the craft in constructing it. They see it as having a much higher quality than I do. Something else shines through in spite of the flaws, or on some level, because of them.

The impossibility of perfection

As a child and even later in years, when I was frustrated at my limitations, my Mother always said to me, « only God can make something perfect ». One idea behind this is that human life and our efforts are always flawed, so we have to simply do our best and accept that the result will never be what we hoped for. Another is that there is another kind of perfection immanent in life which includes the flaws we see. Perhaps that is one way to define art – it’s a vehicle that allows us to see this, appreciate it, and laugh at our foolish notions of perfection.

I’ve spent much of my career as a carpenter correcting the flaws of others. There is the usual catalog of peeling paint, ground in grime, leaking pipes and so on, but I took an enjoyment in this and not only in my work as a carpenter. I’ve repaired so many things I’ve been handed by others or come across in the street and enjoyed repairing them all. For me it’s a sort of inner directive, and of course, it is also satisfying to see my efforts result in a tangible improvement in my life or someone else’s.

One day I was sitting in my room and glanced at a stain in the wall puzzling over it. Suddenly I was transported back a few years to a painful breakup. I was so upset I’d thrown a coffee cup against my wall and watched the liquid drip to the floor. Coming back to the present, I got up and looked around my apartment and could remember several other things that had happened there just by looking at the flaws around me – the time a friend dragged a trunk across the floor, deeply gouging it, or a bump in the wall created carrying my film recorder up the stairs. I began to see flaws as the traces we leave behind in our passing and saw them literally everywhere. I wanted to make a movie out of it at one time, that showed how every nick and scratch, no matter how old, had a story to tell. Our world is densely layered with these traces and stories. It is the ground we walk on.

Tunnel Staircase

In my photography the flaws are even more apparent to me than in my efforts as a carpenter. Although I approach my work in as professional manner as possible, the fact is I’m always trying to learn and do too many different things, usually without a guide. As most do, I learned in school the exacting craft standards of what makes a good exposure, negative or print, and tried to achieve this, but I’ve seen that everything I do is in a way handmade. Each print is different, in a way is born as an individual, rather than stamped out by a perfect reproduction process. I felt instinctively that this was not a defect but a voice beckoning me to follow.

When I did my first 16×20 finished prints in 1989, I made many tests until I came up with a photo paper and chemical process combination that I liked. I ordered a huge amount of the paper, perhaps 25 boxes of 25 sheets each, at great expense but excited at the prospect of printing my images perfectly. When the heavy box was delivered to my door, before I could sign for it, the delivery man hefted the big box and dropped it on its corner. I signed, thinking nothing of it and only weeks later began using them to print. At that point I discovered almost every sheet had its emulsion cracked at one corner, In other words, they were all flawed – some would say ruined – but it was too late to do anything about it. I printed with them anyway, with my Mother’s words ringing in my ears.

I have taken an approach to photography that might seem to a lot of people like it throws the photographic craft right out the window. How can one think you can make a good photo when you don’t even use a real lens? I guess this is where I could say that art truly meets craft, but walks by unconcerned. I felt that one’s eyes are the true camera and so how you see, the sentiments you express, the personal, will all be more important in the end in creating an image than the more craft based notions of proper equipment and best practices. It doesn’t mean I don’t value craft – more the opposite – but craft can only take you so far. Flaws too remain something I combat in my work and life, but I have come to see how much they form the beautiful fabric of our existence.

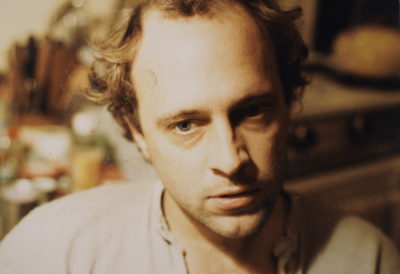

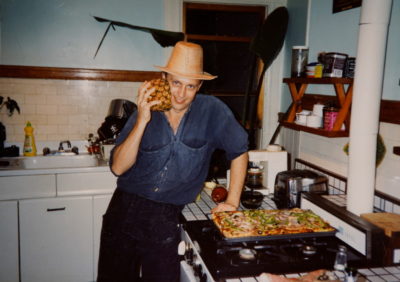

Me, having made an imperfect pizza, that was nonetheless enjoyed by all.

I am quite sure that there are people – smarter, more knowledgeable, skillful or talented than me – who could have done any of the things I’ve done, only much better technically. For me this has always been a given because I understand the nature of mastering a craft. Even for something as simple as carpentry it takes a lifetime, until the body and mind are finely tuned and what you do naturally turns out well. Being who I am, I am all in favor of striving for perfection, but in most things I’m afraid it’s a mirage, and in the end it’s not the measure to rely on, neither for art nor life.

When you look at the sea, is there such a thing as a perfect wave – or can you find a perfect person, plant or tiny flea? Everywhere I look I see individual beings, beautiful in their individuality and more beautiful still when considered together, as a whole. My German cabinetmaking partner wrote a motto on our first business card: Gott Gruß das Handwerk. Although you can translate this in a few ways, I like, « God likes work done by hand » – and I would add, with flaws and all.