ON PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE REAL

Ice on Lake Erie by Robert Schnellbacher

I have spent a lot of time thinking over the years about how people see things differently and inhabit their own personal realities, as well as how much of reality a photograph is capable of capturing. I tried to write about this several times but always grew frustrated in the attempt. It seemed the more I wrote, the more meaning drained away from what I thought I had to say. Here is something I wrote in 1991 – just about all I can quote from one of those documents without cringing:

Far from being simply an objective representation, a photograph is a merging of subjective realities, of the artist, subject and viewer… as Picasso wrote (of a painting) in 1935, « …when it is finished, it still goes on changing, according to the state of mind of whoever is looking at it. A picture lives a life like a living creature… This is natural enough, as the picture lives only through the man who is looking at it. »

Part of the reason that approach never worked for me, is it is clearly a little absurd to try to say anything worthwhile when the topic is « reality ». Unfortunately, that is where I have to go because of the association of photography with the real and how my experimental approach led me to think otherwise. I think the only way that I can navigate through this ridiculous task is to stay as much as possible focused on photography, how to take good photographs, and the creative process. I have to say that this is also ridiculous, but not quite as bad.

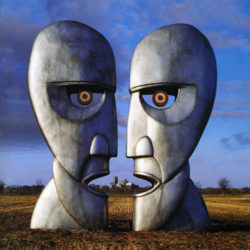

Pink Floyd, The Division Bell (1994) cover

As I was thinking about this all again last night, wondering if I could actually write anything, a song began playing in the café I was hanging out at. An album cover showed on the monitor on the wall from Pink Floyd – the Division Bell.

At the time I was thinking about the inadequacy of the terms conscious and unconscious and of how important sleep and dreaming are to what we call our « self ». Artists rely on this other part of our consciousness a lot – and not only during sleep. This type of thinking is less about following a chain of logic to its conclusion and more about waiting patiently for the idea to come to you. You do this in part by suspending the « conscious » thought process, at least in part – you just stop trying to force your own ideas on the problem. I saw the album cover as a metaphor for the opposition, the duality of consciousness, because one can also look at the image and see one face. The beauty of the image is that one can project upon it any duality one chooses.

It should come as no shock that I rely heavily on the former way of thinking most of the time. It is what makes both craft and science possible, but when I’m stuck, I turn to the other method to see me through. Here, almost anything you say gets squishy, but I’ll use the common phrase. « Something told me » to start with Bob’s photo of ice on Lake Erie.

My sister and Bob in Hawaii

The ice pieces in the picture above remind me of how our attitudes gradually harden and separate from others, just as with ice, as we become « ourselves », but that’s not the reason I think I picked it. I think there’s no better way to talk about photography and the real, than to talk about Bob, my brother in law, who took the picture.

Robert was an extraordinary person, both in his gifts and modesty. Those of us in the family knew about his incredible photographic memory, able to recall events from the distant past – menus, what everyone had eaten, who was there, pictures that hung on the wall – but he kept this mostly hidden, almost as if ashamed. What I learned from my sister after his death was he also had an equally powerful kinesthetic memory. Simply touching an old ticket stub or a photo from the past brought forth a torrent of memories that at times overwhelmed him for hours, unable to move or speak as he vividly re-experienced the past. My sister knew this and tried to protect him from it by hiding things she knew could trigger such an episode in red folders, so he knew that if he ventured there he would at least be prepared.

His memory gifts though went even beyond this. I remember taking the family up a hill above my home in San Francisco during a visit, now called Corona Heights. At one point he wandered off and I later learned that he had a flood of memories from the place although he had never visited it. He said it had been used for ceremonies by Native Americans in the distant past – he could see and hear them, incredible as it may seem. After his death, my sister told me that once on a visit to Arles in France, he told her that they were together there in Roman times, as he insisted they were in other specific times and places. He was a legionnaire and said the quarters were just around the corner. He led her directly there and sure enough there was a plaque describing it. Bear in mind, Bob was not prone to exaggeration nor did he seem in any way a mystic or religious. The only way he was unrealistic was in his underestimation of his own abilities – he disparaged them constantly.

Untitled by Robert Schnellbacher

He was a perfectionist, able to teach himself almost anything, a high level competitive pistol shooter and a life long photographer. Always hard to tell with him because of his modesty, but I got the feeling that he found photography frustrating. We of course had conversations about this, but these would often end with him saying, as if raising an objection to my sanguine comments, « Ah but what to shoot… »?

The way I looked at it, if anyone understood how different reality is from what the photos he took could represent, it was him. I even wondered if photography was like a language that lacked the words necessary to even begin expressing what he saw and felt. In retrospect I think this was both unfair to him and to photography as an art form. I think it’s more likely he approached photography a bit like he did target shooting, which required preparation, training, nerves of steel and taking the shot, and he never confused shooting with life. The conundrum for him was, with photography there is no set target. In this context, it didn’t matter how few techniques he had to work with. Straight black and white photography was an entirely adequate field in which to test himself.

My sister tells me his way of working evolved once he started shooting digitally, partly because there was no longer a cost factor and he shot a lot more abstractions and reflections. He also tried to show what he was feeling when looking at something rather than simply recording it. I am looking at some of them now, since I copied his archive on my last visit, and I am at a loss on what to pick – so many are beautiful while being classically photographic.