ON THE ESSENCE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

« The eyes are the windows of the soul » Leonardo Da Vinci

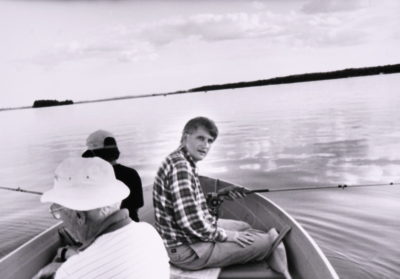

Larry Fishing

Photography is such a technical craft that I think I must begin with science. Photography would not be possible without a scientific understanding of how chemicals and light behave along with an immense amount of engineering to allow us to hold in our hands a miraculous device that can capture a photograph. My brother was trained as a scientist and I can’t tell you how many times he confronted my wooly headed thinking and brought me back to evidence as the ultimate arbiter of evaluating an idea. Nevertheless, as my roommate William would say quoting an African proverb, washing a monkey is a waste of soap.

So it was when I received a visit from a friend of a friend to my home at Walter Street. He was a physicist named Alex from Vienna, Austria. One night we were sitting in my living room talking about science, along with William, who I’d had so many late nights discussing reality, magic and the things we think we know or can’t know. Both of us were eager to get him to admit that science can’t answer many questions. What surprised us both is that he didn’t try to weave or dodge but actually agreed with us.

Candle Flame

He explained to us the difference between having a predictive model and actually understanding something. He used as an example fire, though he said there were plenty of other things for which the same could be said. I’ll just summarize it as follows. We can certainly predict how fire will act under certain conditions but that doesn’t mean we really understand it at all in its essence. He said that we don’t. He also said that if we can’t measure something, science really can’t help us much. I had to revise my ideas of scientific thinking as a result, at least by granting that not all scientists leap from measurement and theory to a sort of almost religious certainty, as I was happy to believe at the time.

Time and my thinking have moved on from those days and perhaps I am remembering it to caution myself. At one time, I was eager to set up and knock down straw men – for photography that the lens was the essence of photography. It seemed to me that it was light rather than the means or fidelity with which one captured it. This answer though didn’t satisfy me. It’s like saying painting is what happens when you mix minerals with oil and put them on cloth. After some years of making photographs and thinking about it, I became convinced that it all came down to the eye and choice. Most photographers at that time didn’t print their own images, so much of what I read about was the choice you make when you frame the image and click the shutter, in the best case during the « perfect moment ».

Living Room at Walter Street with Magnetic Walls

I did print so I was attuned to the other choices you make in the darkroom, which at times are as important as the shot itself. I had also seen from the beginning that the editing process is way more important than either. Out of the hundreds or thousands of images you take, which do you pick to show others? It is the meta-choice that stands over all the others. For that reason, I built magnetic walls in my living room on which I could easily attach my work prints so that I could give each image more time before I decided which spoke to me. This was particularly important for me since I was looking for new types of images, which by their nature I might not recognize as worthy on first glance.

Eye Exam

The problem with choice is it’s a word that refers to a process we have little if any understanding of. It means even less when you consider how short the interval is between the moment you decide to click the shutter and when you do. I think one might as well call it instinct rather than call it a conscious choice, or even grant that it’s sort of random. Even if you prolong the time you consider an image’s merits as I do, it doesn’t actually make the choice you make then any less mysterious.

Can I play it or not?

I welcome « accidents » and I think many other photographers do as well. If a person repeatedly makes something compelling by accident does that make it less artful? For me, random is a word we use to describe complex patterns that we don’t understand. As with Alex’s fire, it’s the best model that science can come up with, but not a real explanation. The same is probably true of anything else I can come up with to explain the inner process of making a photograph or of looking at one.

Today I am inclined to look at cameras in the same light as musical instruments and photographers as people who play them. Anyone can try to make music. It’s not how smart you are – or how expensive or sophisticated the instrument you have that matters. It’s what comes out the other end and whether it pleases you to play it or listen to it. Does it make you want to get up and dance; to cry; to stop up your ears and run from the room – or if you’re trying to play it, throw the damn thing out the window?