WHEN DID EVERYTHING BEGIN?

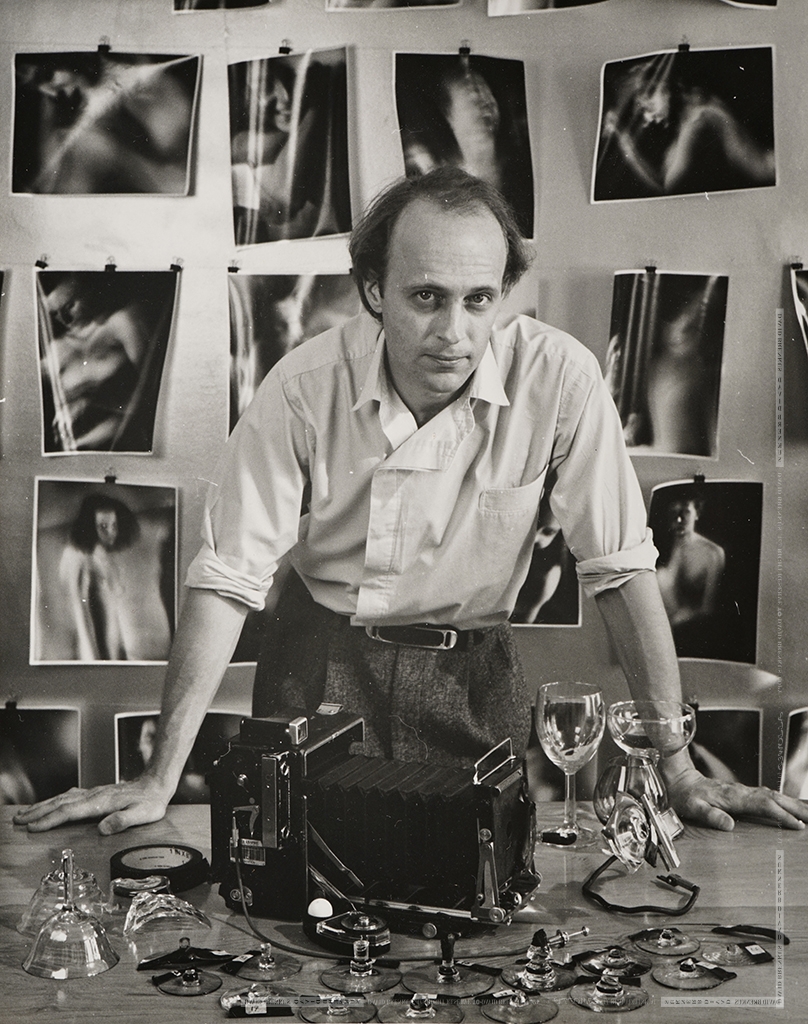

Me with wineglass shot by Janice G. 1989

In 1989, at the age of 32, I decided that I wanted to do something more with my life than working as a carpenter so I was taking classes at City College of San Francisco with the idea of becoming a filmmaker. Up until then I had basically shunned photography. I had never owned a camera and only pushed a shutter a few times in my life. I associated them with tourists hopping out of buses in front of the Grand Canyon, snapping pictures to show they were there, and then hopping back in without ever having really looked where they were. I also viewed photography as sort of tainted since it was used to sell things, and false ideas with them. Finally I had another kind of discomfort with it which was altogether vague, below the surface. Everything had led me to believe that we really see differently while photography seems to show the opposite. Cinema though was another thing entirely to me – it was story telling, world building, and intense drama.

Early on during these film classes, I felt drawn to the technical side and to experimentation. I developed my own film and began playing a little with the chemistry but became convinced that I needed to take a beginning photography class to better understand the film process.

You see, Super-8 film, which is all we had in those days to make inexpensive movies, was all direct positive while professional movies all started with negatives, about which I knew nothing. So I paused my cinema classes and took a beginning large format black and white photo class in addition to a history of photography class.

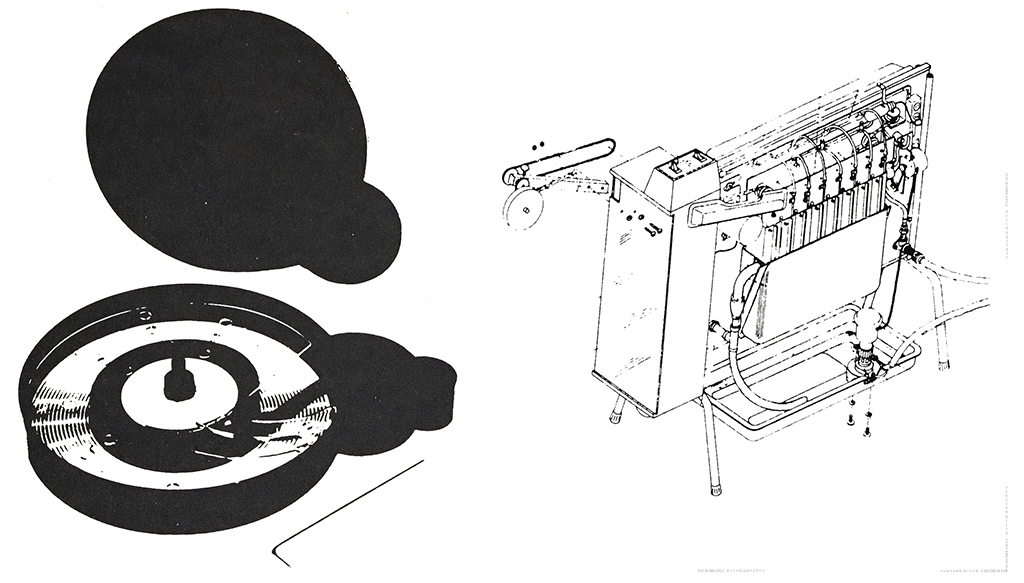

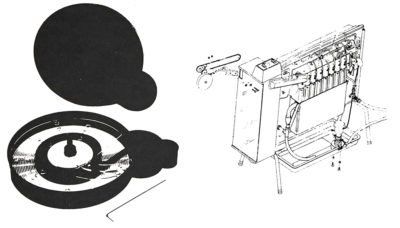

Two methods I used for developing Super-8 film: Single roll tank and 16mm developing machine I adapted to super-8

It was during those classes that it all started. There was an anecdote floating around my head from a history lecture I’d had earlier. The teacher, Jim Doukas, had shown a slide of an otherwise unremarkable photo taken by Man Ray of Matisse using one of Matisse’s own eyeglasses as the lens, since Man Ray had forgotten to bring any to the session. For me it was a surprise that you could actually take a picture without using a commercial lens. Then during the beginning photography class we were being explained our first assignment – how to make a photogram. The same teacher was exhorting us to rid ourselves of preconceptions and to not just plop down objects on the photo paper without thinking about it. He said, remember there is always something new you can discover. For a person like me, this was like waving a red flag in front of a bull.

Matisse shot by Man Ray using Matisse’s eyeglasses 1936?

His voice faded out and I started to daydream. I began to wonder what it would look like if you had a fluid lens, one whose shape you could change? It suddenly struck me that optics was the most fundamental aspect of photography but never had it been systematically used as the variable.

I had this postcard on my desk for years – Man Ray, solarized self portrait 1931

I became excited and ran home to freeze some water into different shapes to see if I could put them in front of the camera instead of spectacles as Man Ray had done as a useful expedient. That idea didn’t work – the ice just melted in my hand and frosted up to boot – so I began searching the house for pieces of glass: pitchers, vases, tumblers, wineglasses and so on, that I could try focusing with instead. To my surprise and excitement, I found I could focus using found glass but at the same time I saw imperfections or deformations that expressed something else to me as I tilted them, something that resonated and called to me. Wineglasses worked best, especially if I broke them at the stem and just used the bottom since they are all a bit lens shaped. Happily the camera I’d bought for the class had included a shutter of its own so removing the normal lens was not a problem in making precise exposures, which was another factor that caused me to try it.

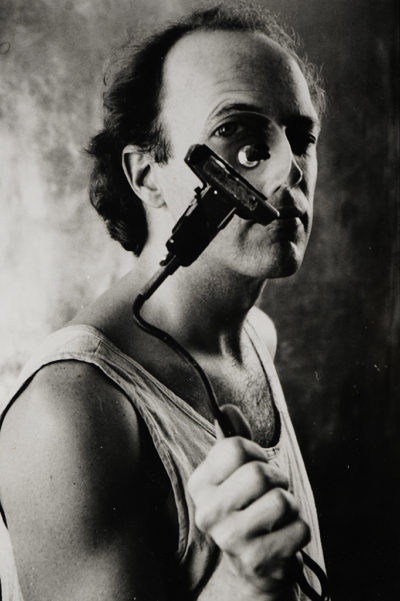

Me in 1990 with Wineglass lenses shot by Michael Brennan

I went from thrift store to thrift store buying wineglasses to experiment with, often paying 25 cents for a „lens“, which amused me, as it seemed you had to spend thousands to get a good lens or a great picture. Then I took home the bag of wineglasses and tried to focus on a mannequin head, tilting each wineglass one way or the other to see what effect it had. If it was promising I used a little hammer to break off the stem and added it to the collection of lenses I would shoot with, numbering the lens with a code on a piece of masking tape.

One of the first shots I took using one of these wineglass lenses was of Greta, a close friend. I taped the wineglass bottom to the baseboard of the 4×5 speed graphic camera, tilted it and secured the angle with another piece of tape and shot her next to her window in her apartment. The result encouraged me greatly when I printed it. I saw an otherworldly quality in it as well as a sort of style I had never seen. It was photographic but somehow not.

Greta Window 1989

I began using some cinema equipment I had to hold other wineglasses in front of the one I had taped to the camera front and I found every movement of any of the lens elements produced completely different results. Everything mattered: the pieces used, their angles, positions, and relative position in relation to the dime sized hole in the baseboard which was my aperture. Needless to say anyone I shot had to stay absolutely still, as in the early years of photography.

I could see these results without capturing them on film as I moved each one because these kinds of cameras have a ground glass upon which the image is seen directly, though upside down and reversed. This is the kind of camera where you have to bend down and hold a dark cloth over your head to block out all the light so that you can see the image that forms on the ground glass.

My wineglass setup using two lens elements taken by a teacher at CCSF (Janice G) 1989

I called it a variable axis optical system. The great thing is the act of focusing became more complex. Rather than one simple focus, I had the ability to search through many for one that spoke to me.