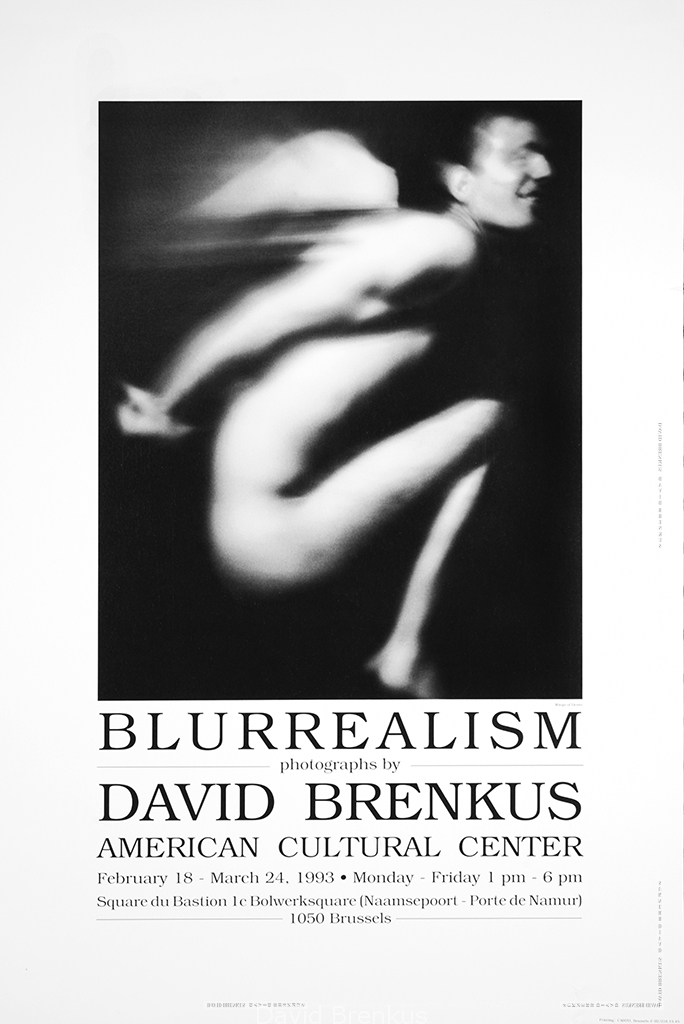

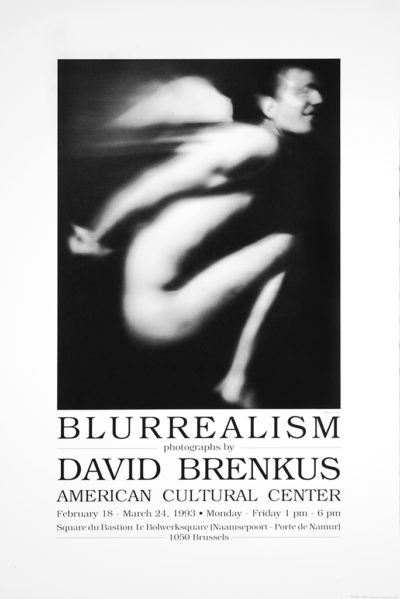

ON BLURREALISM

Blurrealism Poster 1993

Bombarded and over stimulated as we are by meaningless or contradictory information, as our society approaches a state of schizophrenia, we must try to see through this blur of artificiality and appearances. Inevitably this involves eliciting and assimilating the perceptions of others, as well as listening for our own inner voice, for reality is a process, a dialogue, a conversation, not a static or one sided image. As should be clear from the above, the object of my work is not a new aesthetics or style, but a way of seeing, hopefully beneath the surface noise, a Blurrealism.

David Brenkus 1990

Blurrealism is a word I made up to describe what I was doing with my art nearly 30 years ago. Although I thought of it in the same context as Surrealism – an art movement in other words, and I was being a little tongue in cheek when I did so – it is more accurate to say that it represents a set of thoughts I’ve had throughout my life. It might jokingly be called a philosophy of the lens, since I began using the term when I started making my own radically different kinds of lenses.

Before I began taking photos myself I was deeply ambivalent about photography. One thing that bothered me was I thought people tended to confuse photography with reality because a machine is used rather than a hand and pencil. This in turn represented a more general concern I had about our society and the way we look at things. Photographs are usually highly realistic, but drawings or paintings can be too. In my mind I had trouble seeing the difference between them. For me they were all pictures, so it is little wonder that my work has played at the boundary between the two. Realism and reality though are not the same at all.

Our Sun (Wikimedia images)

We have to be clear at the outset what a photograph is. The Greek roots of the word translate to a drawing with light, implicitly within the visible spectrum. Light however, is agnostic regarding realism – it simply is. Light is also far from the only thing that can be used to give us a window into reality. Realism is imparted to a photograph by the lens – based upon how our eyes work optically – not light itself. Of course, realism in a painting works the same way. Painters can rely on the optics of the eye as well, but few feel restricted to this approach. For virtually everyone though, it is still implicit that photographic lenses must be realistic. This was not the case for me. I felt instinctively that questioning that central premise could accomplish several goals simultaneously. If I could create new types of lenses that worked, it could provide me the freedom of expression that a painter has, while clearing up a misconception about the role of photography as an art medium. It could also embody ideas I had about reality, which has many more layers to it than a realistic depiction can show.

Apart from the lens, there is however another aspect of classical photography that links it closer in our minds with reality than a painting does, which is connected to the mechanical nature of taking a picture. A realistic painting creates the illusion that we are looking at a moment in time, but a single exposure photograph is literally captured in a moment. We sense that we are not only looking at a scene but a moment in time, and it lends a photograph a greater sense that we are looking at reality. I love this aspect of photography and have exploited it myself because I believe that there is significance in every moment. The question I had was, if you created and used other types of lenses, could you capture some of the other layers of reality that are there in that moment but not seen?

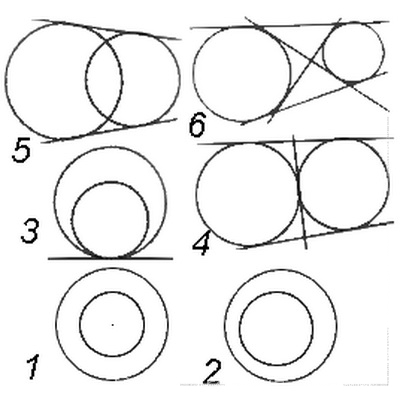

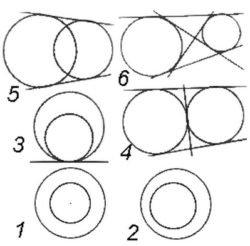

Wineglass variable axis optics

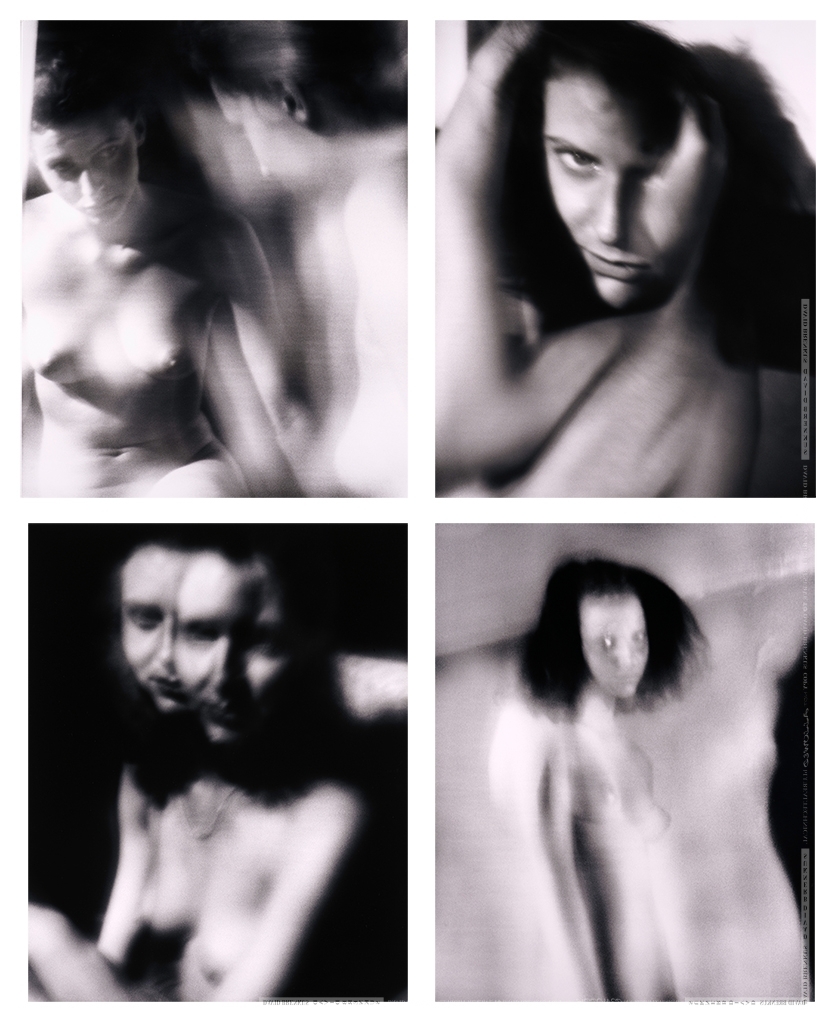

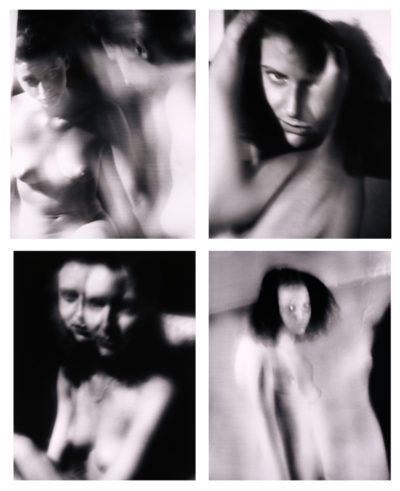

The outward appearance of a person, such as you capture in a normal photograph, seems one dimensional or superficial if you have some insight into the things going on inside that person or within yourself. Rather than being stable and unitary – what a person looks like from the outside – we are constantly changing inside and have hidden personas interacting with each other and the outside world. When you speak with a person it is fair to ask to whom you are speaking. I invented what I called variable axis optics in response to the bias of the normal lens as I began experimenting with the wineglass lenses to photograph people.

The portraits I created with the lenses looked as if they revealed windows into the inner states of the persons I photographed. The sometimes radical degree of deformation suggested how much more important those inner states were than the outer appearance a normal photograph could show. This phase of my work reached its fullest expression in the series “21” where I showed 21 photos of a 21 year old woman using the wineglass lenses. It can be a bit shocking to recognize that these are all single shot photographs of the same person, but that is the point. You can look at them and ask yourself, who are all of these people, and can they really be the same person? Am I seeing a wounded child, a proud achiever, a wooly idealist, a combination of others unknown, two of them simultaneously?

Four photos from the series 21

Sinking of Titanic (Wikimedia Images)

I was able to do this by using a different kind of lens, but it would be a mistake to simply use the interpretation above as a guide to viewing my photos. For me, the complexity of human psychology was just the tip of an iceberg, an example of the complexity of reality and how much of it is unseen. I began here with psychology, because it is easily related to my first photos, but there are lots of other subjects that play a similar role. Each of these subjects has its own language, history and controversies. If you learn any one of them, certain mysteries disappear, but if it is your only point of reference, it is a little like always viewing things through one lens, as if you can only look through a telescope while walking down the street. Sooner or later your sense of reality will come up against the massive part of the iceberg you can’t see.

I saw an obvious corollary that applies to photography and visual art. It is that people see differently, and how they see art or simple photographs is no exception. People can look at almost anything and come away with different feelings and thoughts which are mostly hidden and therefore easy to ignore. They can see the Madonna in a loaf of bread. I don’t mean to imply that is ridiculous. I tend to see significance in small things others would consider random chance, and obviously, I believe that even a very blurry lens can be of value. Photography, in common parlance, does not. The idea that the surface you see is reality, and that we all see it quite the same, to me was highly unrealistic.

Diagram (Wikimedia Images)

Making the photos with the new lenses helped me understand that a photograph is not simply a representation of a thing or person but a nexus or set of relationships. No one could probably have taken those pictures but me since they were the result of the relationship between me and those I photographed. This is simply a lot easier to see because my lenses magnified it – of what I was bringing to the conversation and what the model did as well. Since each person who views them will see them differently, they are also in this relationship themselves. Normal photography, because it has always used the same sort of lens, masks this and fools us into thinking we are seeing objects existing on their own rather than something more complex – a strange process where everything is interconnected in mysterious ways.

Rite of Passage 1997 (Multi Exposure)

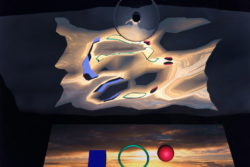

However, the other aspect of classical photography I mentioned also masks the complexity of reality. If you make a simple single exposure you can too easily get the feeling that life is serial, that only one thing happens at a time. In reality, many things are happening at many different levels simultaneously. This is why I turned to multiple exposures and the layering of images in my work. I felt that building up an image from layers better suggested the combination of the seen and unseen that is occurring in every moment.

There is so much more hidden from us than is apparent from the surface, and I’m not only talking about the behavior and motivations of people. This is why I called what I was doing Blurrealism, rather than Psycho-Photography. The funny thing is, sometimes literally a different lens can be used to shed light on it. The easiest example I can think of is the microscope, where simply looking through it reveals entire worlds teaming with creatures we would never suspect were there, which on its own blows up our simplest surface notion of reality.

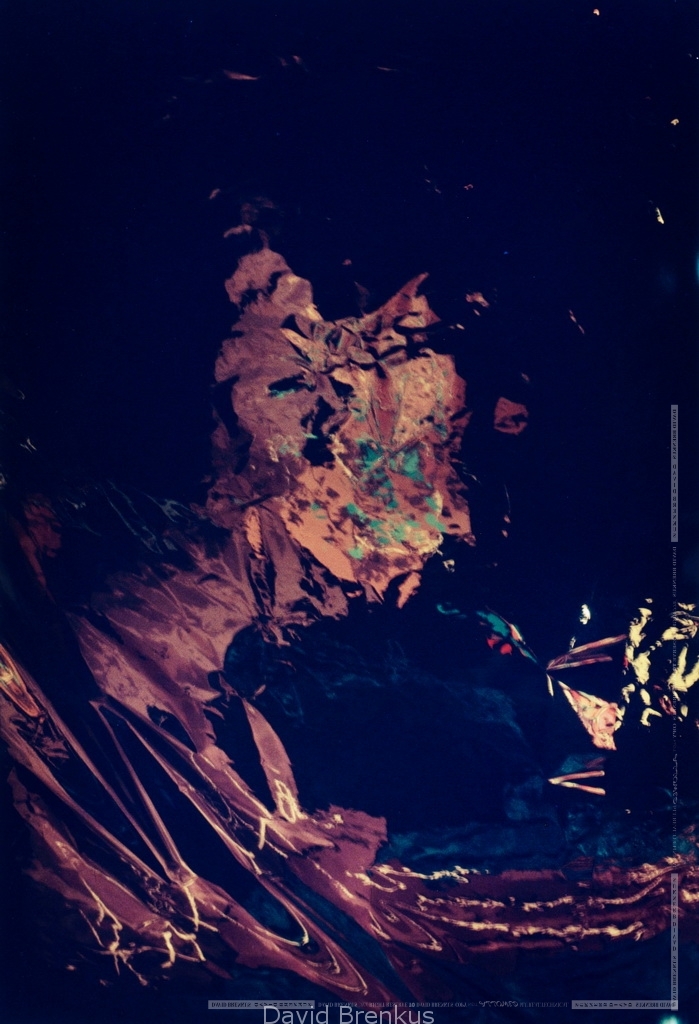

Contemplation 1996 (Mylar Mirror shot)

By the time I was 32 when I began making photos, I’d experienced enough strange things in my life that I thought that the existence of hidden worlds, such as we see through a microscope, could apply to planes of reality we don’t now associate with the physical, which like so many people, I sensed were there. So when I looked at the wineglass photos, I didn’t only ask who am I seeing but what am I seeing? This became even more the case when I began using a different kind of lens than the wineglasses and started working with abstraction. Abstraction lends itself to portraying the hidden sides of reality and becomes a canvas upon which we can project our own questions.

The way the wineglass lenses work optically is they don’t collect light from one perfectly focused perspective. This is how the deformations and overlaying of images can occur. I began using a deformable plastic Mylar mirror to exaggerate this paradigm. The idea was to create a lens that captures light from many directions and perspectives. At the same time, it fragments and merges them into a whole, a photograph. I thought this an apt metaphor for how we could see reality. At the same time I had to wonder, because there are other parts of reality that exist beyond our awareness or comprehension, could I be seeing something more than a metaphor, a window into something real, if nowhere else, inside of me?

Sunset #1 – Sunset Setup 2000-09

The Sunset series was the culmination of this process when I converted the physical wineglass and Mylar mirror into a digital 3D model that I could manipulate much easier. Luckily I used the same simple objects which I would photograph – a sphere, torus and cube placed on top of an image of a sunset – and never moved them. I only changed the shape of the virtual lens and mirror I used as my optical system and the placement of the virtual camera.

Sunset #27 – Sun33d12h-RTP 2000-09

The result to me was even more startling than the 21 photos of one person, for the difference between what I was photographing and the photographs produced was so much greater. How could all of that be produced from those simple objects? It was like the big bang, when our entire universe came out of nothing. It made me wonder, could this type of phenomenon, this instant complexity, represent something embedded into reality?

You could say that unlike the Surrealists, I am not reacting in my art to the idea of the unconscious but that of complexity because of how the world was changing when I grew up. Needless to say, the knowledge at our fingertips and the complexity of our lives has exploded since the time I first started taking pictures in 1989. It is difficult to grasp complexity, and can be uncomfortable to do so. No one enjoys living with doubt as a companion. It’s hard enough just dealing with the rent and knowing whether or not someone’s lying to you, without entertaining notions of dimensions of reality we can’t reconcile with our own beliefs. Some people are in such despair that they think only an artificial intelligence can sort it out. I reject this pessimism because fortunately, our minds have something no computer has to help us weigh this complexity – intuition and a conscience – our inner light. Sadly, this too can take the form of a two edged sword as we can only approach this with our own lenses too, at least initially.

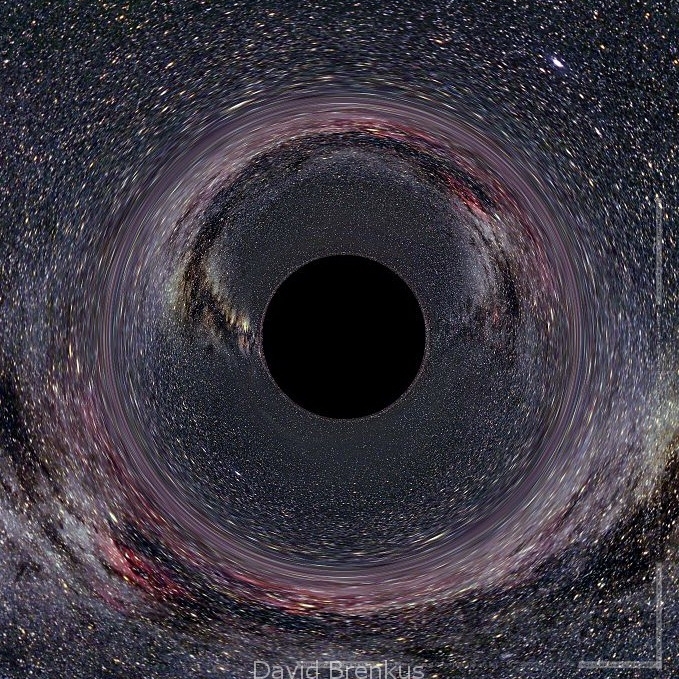

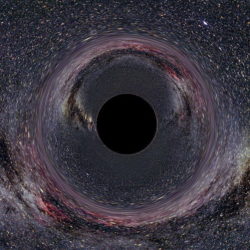

Black Hole (Wikimedia Images)

People can have a fanatical devotion to their perceptual lenses – to what layers of meaning they are willing or able to see, and their gravitational force can then pass a threshold as the myopia of the perspective shrinks. Eventually life has a way restoring the balance, of forcing us to see beyond ourselves and our surface perspectives, usually when we have to confront the consequences of our individual or collective actions, but almost certainly when we have to face our own decline and death. When we are in thrall to it though, it can become a destructive and entropic process.

Every word said will be scrutinized in a war against all the others. One is not allowed to show doubt, or confusion, or change one’s mind, but only to fall in line, abase oneself, salute and join in the combat. It can become like a black hole of meaning dragging everything around into it to be consumed. As an artist, it seems sometimes that if you are not making art about the raging conflicts of the day, you are not “saying” anything important. During such times I think it is especially important to examine our own lenses, to take stock of what others we may have, and ask of ourselves more.

When we look at a sunset, or anything else that radiates beauty, I think we are responding to a deeper layer within us that is beyond language. For this reason, the awe we feel is difficult or impossible to express. It short circuits the thorny problems of our words and permits us to put our weapons of logic down for a second, along with our cherished polar positions. I can’t help but think that this is another, very different sort of language – one reality is speaking to us all the time. Nothing is stopping us from freezing time with a photograph, from prolonging the eternity of the moment by pausing to ask what it shows us about ourselves and our own small slice of reality.

Me learning to juggle, aged 17?

What does it say about our culture that the art I make seems to be all about the new, some new technique or idea, instead of a simple sunset? I think it shows the blind spot at the center of our culture and our difficulty in reconciling the old with the new. It is also another way to understand the lenses I created. A fragmentary approach to art reflects not only complexity we need to grasp, but the pain and confusion it causes. As artists, we can’t wave a magic wand any more than anyone can, but we can try to help people to lay aside their confusion for a short while and feel again that we are only part of something that is much greater and more beautiful than our individual selves, to dance to the beat we all feel within and around us.

When I was young, people used to say that you had to widen your perspective. I don’t think that’s enough anymore. We have to combine perspectives and be willing to use different and unfamiliar lenses – and learn to juggle them. I think it’s time for each of us to look through some other ones and discover what they can show us, to join into the conversation that is embedded within reality. Perhaps looking through different ones will help us all see below the surface appearances that trick and obscure our understandings of reality, which is what Blurrealism is all about to me.