ON BLURREALISM Bombarded and over stimulated as we are by meaningless or contradictory information, as our society approaches a state of schizophrenia, we must try to see through this blur of artificiality and appearances. Inevitably this involves eliciting and assimilating the perceptions of others, as well as listening for our own inner voice, for reality […]

ON BLURREALISM

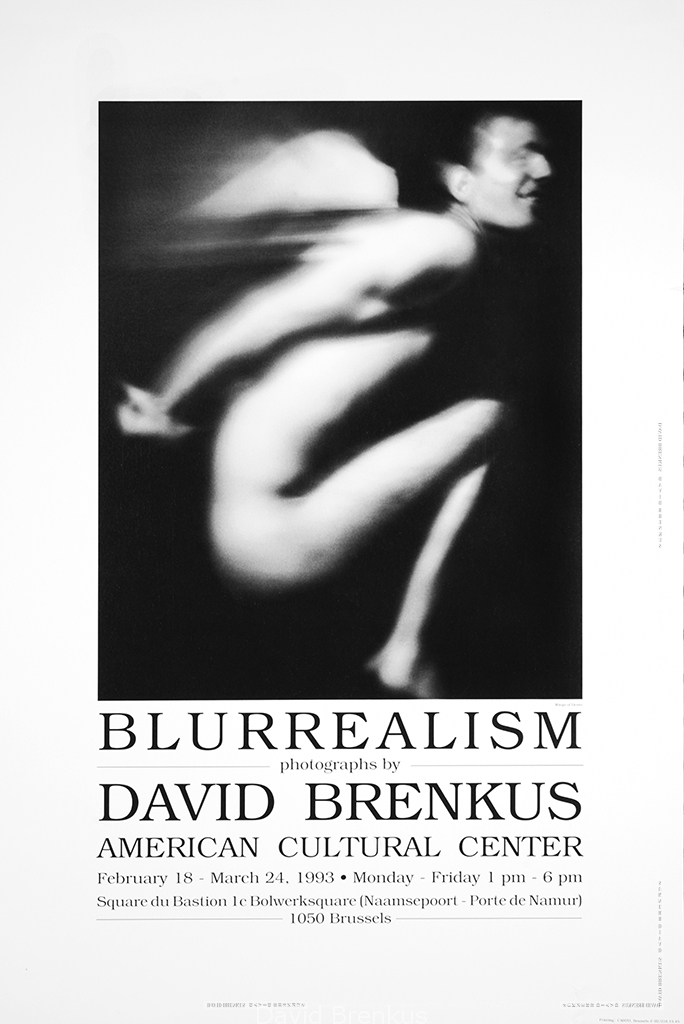

Blurrealism Poster 1993Bombarded and over stimulated as we are by meaningless or contradictory information, as our society approaches a state of schizophrenia, we must try to see through this blur of artificiality and appearances. Inevitably this involves eliciting and assimilating the perceptions of others, as well as listening for our own inner voice, for reality is a process, a dialogue, a conversation, not a static or one sided image. As should be clear from the above, the object of my work is not a new aesthetics or style, but a way of seeing, hopefully beneath the surface noise, a Blurrealism.

David Brenkus 1990

Blurrealism is a word I made up to describe what I was doing with my art nearly 30 years ago. Although I thought of it in the same context as Surrealism – an art movement in other words, and I was being a little tongue in cheek when I did so – it is more accurate to say that it represents a set of thoughts I’ve had throughout my life. It might jokingly be called a philosophy of the lens, since I began using the term when I started making my own radically different kinds of lenses.

Before I began taking photos myself I was deeply ambivalent about photography. One thing that bothered me was I thought people tended to confuse photography with reality because a machine is used rather than a hand and pencil. This in turn represented a more general concern I had about our society and the way we look at things. Photographs are usually highly realistic, but drawings or paintings can be too. In my mind I had trouble seeing the difference between them. For me they were all pictures, so it is little wonder that my work has played at the boundary between the two. Realism and reality though are not the same at all.

Our Sun (Wikimedia images)We have to be clear at the outset what a photograph is. The Greek roots of the word translate to a drawing with light, implicitly within the visible spectrum. Light however, is agnostic regarding realism – it simply is. Light is also far from the only thing that can be used to give us a window into reality. Realism is imparted to a photograph by the lens – based upon how our eyes work optically – not light itself. Of course, realism in a painting works the same way. Painters can rely on the optics of the eye as well, but few feel restricted to this approach. For virtually everyone though, it is still implicit that photographic lenses must be realistic. This was not the case for me. I felt instinctively that questioning that central premise could accomplish several goals simultaneously. If I could create new types of lenses that worked, it could provide me the freedom of expression that a painter has, while clearing up a misconception about the role of photography as an art medium. It could also embody ideas I had about reality, which has many more layers to it than a realistic depiction can show.

Apart from the lens, there is however another aspect of classical photography that links it closer in our minds with reality than a painting does, which is connected to the mechanical nature of taking a picture. A realistic painting creates the illusion that we are looking at a moment in time, but a single exposure photograph is literally captured in a moment. We sense that we are not only looking at a scene but a moment in time, and it lends a photograph a greater sense that we are looking at reality. I love this aspect of photography and have exploited it myself because I believe that there is significance in every moment. The question I had was, if you created and used other types of lenses, could you capture some of the other layers of reality that are there in that moment but not seen?

Wineglass variable axis opticsThe outward appearance of a person, such as you capture in a normal photograph, seems one dimensional or superficial if you have some insight into the things going on inside that person or within yourself. Rather than being stable and unitary – what a person looks like from the outside – we are constantly changing inside and have hidden personas interacting with each other and the outside world. When you speak with a person it is fair to ask to whom you are speaking. I invented what I called variable axis optics in response to the bias of the normal lens as I began experimenting with the wineglass lenses to photograph people.

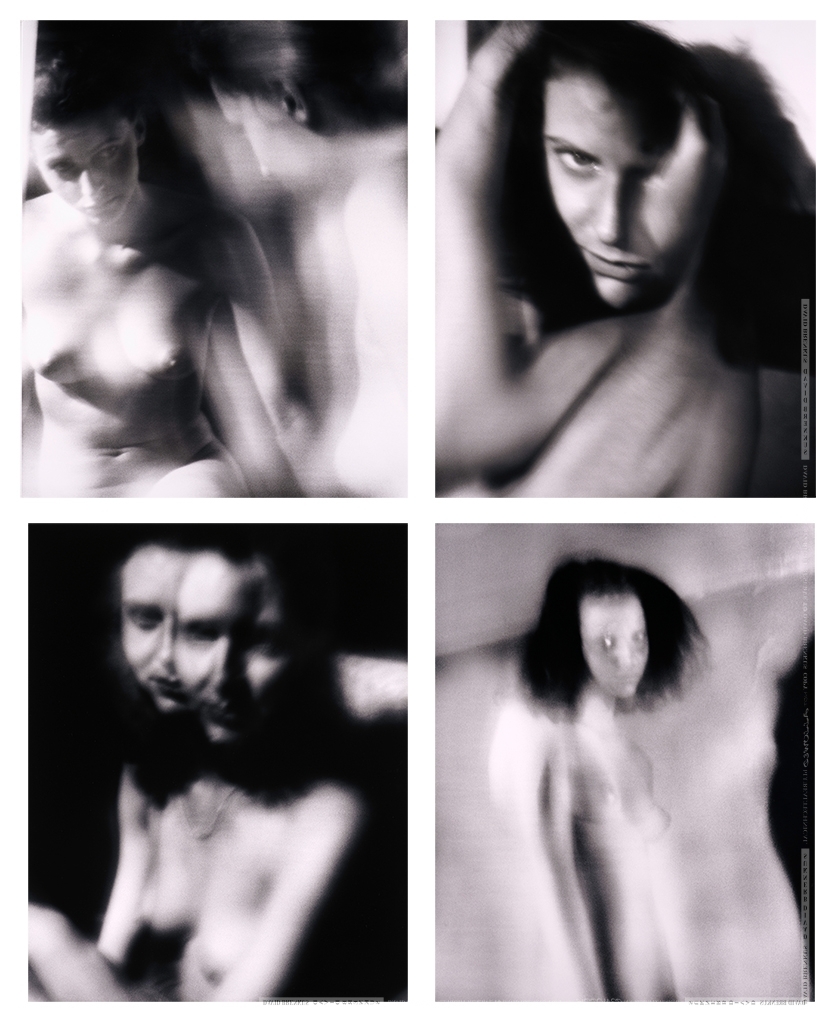

The portraits I created with the lenses looked as if they revealed windows into the inner states of the persons I photographed. The sometimes radical degree of deformation suggested how much more important those inner states were than the outer appearance a normal photograph could show. This phase of my work reached its fullest expression in the series « 21 » where I showed 21 photos of a 21 year old woman using the wineglass lenses. It can be a bit shocking to recognize that these are all single shot photographs of the same person, but that is the point. You can look at them and ask yourself, who are all of these people, and can they really be the same person? Am I seeing a wounded child, a proud achiever, a wooly idealist, a combination of others unknown, two of them simultaneously?

Four photos from the series 21 Sinking of Titanic (Wikimedia Images)I was able to do this by using a different kind of lens, but it would be a mistake to simply use the interpretation above as a guide to viewing my photos. For me, the complexity of human psychology was just the tip of an iceberg, an example of the complexity of reality and how much of it is unseen. I began here with psychology, because it is easily related to my first photos, but there are lots of other subjects that play a similar role. Each of these subjects has its own language, history and controversies. If you learn any one of them, certain mysteries disappear, but if it is your only point of reference, it is a little like always viewing things through one lens, as if you can only look through a telescope while walking down the street. Sooner or later your sense of reality will come up against the massive part of the iceberg you can’t see.

I saw an obvious corollary that applies to photography and visual art. It is that people see differently, and how they see art or simple photographs is no exception. People can look at almost anything and come away with different feelings and thoughts which are mostly hidden and therefore easy to ignore. They can see the Madonna in a loaf of bread. I don’t mean to imply that is ridiculous. I tend to see significance in small things others would consider random chance, and obviously, I believe that even a very blurry lens can be of value. Photography, in common parlance, does not. The idea that the surface you see is reality, and that we all see it quite the same, to me was highly unrealistic.

Diagram (Wikimedia Images)Making the photos with the new lenses helped me understand that a photograph is not simply a representation of a thing or person but a nexus or set of relationships. No one could probably have taken those pictures but me since they were the result of the relationship between me and those I photographed. This is simply a lot easier to see because my lenses magnified it – of what I was bringing to the conversation and what the model did as well. Since each person who views them will see them differently, they are also in this relationship themselves. Normal photography, because it has always used the same sort of lens, masks this and fools us into thinking we are seeing objects existing on their own rather than something more complex – a strange process where everything is interconnected in mysterious ways.

Rite of Passage 1997 (Multi Exposure)However, the other aspect of classical photography I mentioned also masks the complexity of reality. If you make a simple single exposure you can too easily get the feeling that life is serial, that only one thing happens at a time. In reality, many things are happening at many different levels simultaneously. This is why I turned to multiple exposures and the layering of images in my work. I felt that building up an image from layers better suggested the combination of the seen and unseen that is occurring in every moment.

There is so much more hidden from us than is apparent from the surface, and I’m not only talking about the behavior and motivations of people. This is why I called what I was doing Blurrealism, rather than Psycho-Photography. The funny thing is, sometimes literally a different lens can be used to shed light on it. The easiest example I can think of is the microscope, where simply looking through it reveals entire worlds teaming with creatures we would never suspect were there, which on its own blows up our simplest surface notion of reality.

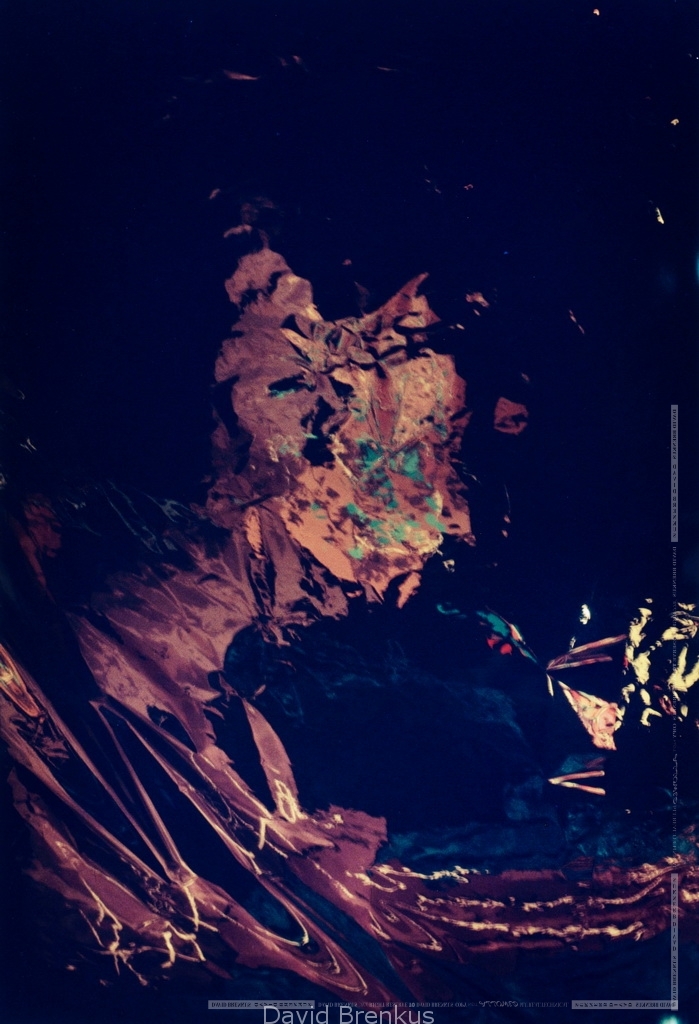

Contemplation 1996 (Mylar Mirror shot)By the time I was 32 when I began making photos, I’d experienced enough strange things in my life that I thought that the existence of hidden worlds, such as we see through a microscope, could apply to planes of reality we don’t now associate with the physical, which like so many people, I sensed were there. So when I looked at the wineglass photos, I didn’t only ask who am I seeing but what am I seeing? This became even more the case when I began using a different kind of lens than the wineglasses and started working with abstraction. Abstraction lends itself to portraying the hidden sides of reality and becomes a canvas upon which we can project our own questions.

The way the wineglass lenses work optically is they don’t collect light from one perfectly focused perspective. This is how the deformations and overlaying of images can occur. I began using a deformable plastic Mylar mirror to exaggerate this paradigm. The idea was to create a lens that captures light from many directions and perspectives. At the same time, it fragments and merges them into a whole, a photograph. I thought this an apt metaphor for how we could see reality. At the same time I had to wonder, because there are other parts of reality that exist beyond our awareness or comprehension, could I be seeing something more than a metaphor, a window into something real, if nowhere else, inside of me?

Sunset #1 – Sunset Setup 2000-09The Sunset series was the culmination of this process when I converted the physical wineglass and Mylar mirror into a digital 3D model that I could manipulate much easier. Luckily I used the same simple objects which I would photograph – a sphere, torus and cube placed on top of an image of a sunset – and never moved them. I only changed the shape of the virtual lens and mirror I used as my optical system and the placement of the virtual camera.

Sunset #27 – Sun33d12h-RTP 2000-09The result to me was even more startling than the 21 photos of one person, for the difference between what I was photographing and the photographs produced was so much greater. How could all of that be produced from those simple objects? It was like the big bang, when our entire universe came out of nothing. It made me wonder, could this type of phenomenon, this instant complexity, represent something embedded into reality?

You could say that unlike the Surrealists, I am not reacting in my art to the idea of the unconscious but that of complexity because of how the world was changing when I grew up. Needless to say, the knowledge at our fingertips and the complexity of our lives has exploded since the time I first started taking pictures in 1989. It is difficult to grasp complexity, and can be uncomfortable to do so. No one enjoys living with doubt as a companion. It’s hard enough just dealing with the rent and knowing whether or not someone’s lying to you, without entertaining notions of dimensions of reality we can’t reconcile with our own beliefs. Some people are in such despair that they think only an artificial intelligence can sort it out. I reject this pessimism because fortunately, our minds have something no computer has to help us weigh this complexity – intuition and a conscience – our inner light. Sadly, this too can take the form of a two edged sword as we can only approach this with our own lenses too, at least initially.

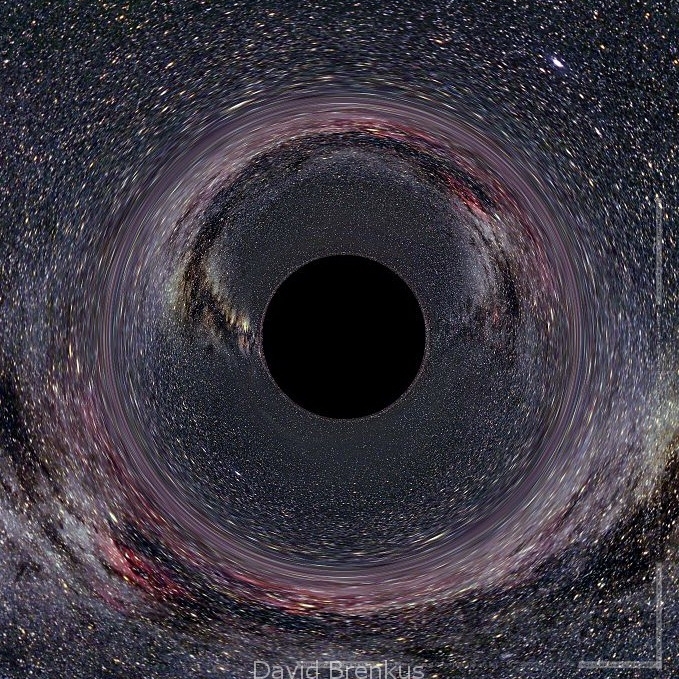

Black Hole (Wikimedia Images)People can have a fanatical devotion to their perceptual lenses – to what layers of meaning they are willing or able to see, and their gravitational force can then pass a threshold as the myopia of the perspective shrinks. Eventually life has a way restoring the balance, of forcing us to see beyond ourselves and our surface perspectives, usually when we have to confront the consequences of our individual or collective actions, but almost certainly when we have to face our own decline and death. When we are in thrall to it though, it can become a destructive and entropic process.

Every word said will be scrutinized in a war against all the others. One is not allowed to show doubt, or confusion, or change one’s mind, but only to fall in line, abase oneself, salute and join in the combat. It can become like a black hole of meaning dragging everything around into it to be consumed. As an artist, it seems sometimes that if you are not making art about the raging conflicts of the day, you are not « saying » anything important. During such times I think it is especially important to examine our own lenses, to take stock of what others we may have, and ask of ourselves more.

When we look at a sunset, or anything else that radiates beauty, I think we are responding to a deeper layer within us that is beyond language. For this reason, the awe we feel is difficult or impossible to express. It short circuits the thorny problems of our words and permits us to put our weapons of logic down for a second, along with our cherished polar positions. I can’t help but think that this is another, very different sort of language – one reality is speaking to us all the time. Nothing is stopping us from freezing time with a photograph, from prolonging the eternity of the moment by pausing to ask what it shows us about ourselves and our own small slice of reality.

Me learning to juggle, aged 17?What does it say about our culture that the art I make seems to be all about the new, some new technique or idea, instead of a simple sunset? I think it shows the blind spot at the center of our culture and our difficulty in reconciling the old with the new. It is also another way to understand the lenses I created. A fragmentary approach to art reflects not only complexity we need to grasp, but the pain and confusion it causes. As artists, we can’t wave a magic wand any more than anyone can, but we can try to help people to lay aside their confusion for a short while and feel again that we are only part of something that is much greater and more beautiful than our individual selves, to dance to the beat we all feel within and around us.

When I was young, people used to say that you had to widen your perspective. I don’t think that’s enough anymore. We have to combine perspectives and be willing to use different and unfamiliar lenses – and learn to juggle them. I think it’s time for each of us to look through some other ones and discover what they can show us, to join into the conversation that is embedded within reality. Perhaps looking through different ones will help us all see below the surface appearances that trick and obscure our understandings of reality, which is what Blurrealism is all about to me.

ON THE ESSENCE OF PHOTOGRAPHY « The eyes are the windows of the soul » Leonardo Da Vinci Photography is such a technical craft that I think I must begin with science. Photography would not be possible without a scientific understanding of how chemicals and light behave along with an immense amount of engineering to allow us […]

ON THE ESSENCE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

« The eyes are the windows of the soul » Leonardo Da Vinci

Larry FishingPhotography is such a technical craft that I think I must begin with science. Photography would not be possible without a scientific understanding of how chemicals and light behave along with an immense amount of engineering to allow us to hold in our hands a miraculous device that can capture a photograph. My brother was trained as a scientist and I can’t tell you how many times he confronted my wooly headed thinking and brought me back to evidence as the ultimate arbiter of evaluating an idea. Nevertheless, as my roommate William would say quoting an African proverb, washing a monkey is a waste of soap.

So it was when I received a visit from a friend of a friend to my home at Walter Street. He was a physicist named Alex from Vienna, Austria. One night we were sitting in my living room talking about science, along with William, who I’d had so many late nights discussing reality, magic and the things we think we know or can’t know. Both of us were eager to get him to admit that science can’t answer many questions. What surprised us both is that he didn’t try to weave or dodge but actually agreed with us.

Candle FlameHe explained to us the difference between having a predictive model and actually understanding something. He used as an example fire, though he said there were plenty of other things for which the same could be said. I’ll just summarize it as follows. We can certainly predict how fire will act under certain conditions but that doesn’t mean we really understand it at all in its essence. He said that we don’t. He also said that if we can’t measure something, science really can’t help us much. I had to revise my ideas of scientific thinking as a result, at least by granting that not all scientists leap from measurement and theory to a sort of almost religious certainty, as I was happy to believe at the time.

Time and my thinking have moved on from those days and perhaps I am remembering it to caution myself. At one time, I was eager to set up and knock down straw men – for photography that the lens was the essence of photography. It seemed to me that it was light rather than the means or fidelity with which one captured it. This answer though didn’t satisfy me. It’s like saying painting is what happens when you mix minerals with oil and put them on cloth. After some years of making photographs and thinking about it, I became convinced that it all came down to the eye and choice. Most photographers at that time didn’t print their own images, so much of what I read about was the choice you make when you frame the image and click the shutter, in the best case during the « perfect moment ».

Living Room at Walter Street with Magnetic WallsI did print so I was attuned to the other choices you make in the darkroom, which at times are as important as the shot itself. I had also seen from the beginning that the editing process is way more important than either. Out of the hundreds or thousands of images you take, which do you pick to show others? It is the meta-choice that stands over all the others. For that reason, I built magnetic walls in my living room on which I could easily attach my work prints so that I could give each image more time before I decided which spoke to me. This was particularly important for me since I was looking for new types of images, which by their nature I might not recognize as worthy on first glance.

Eye ExamThe problem with choice is it’s a word that refers to a process we have little if any understanding of. It means even less when you consider how short the interval is between the moment you decide to click the shutter and when you do. I think one might as well call it instinct rather than call it a conscious choice, or even grant that it’s sort of random. Even if you prolong the time you consider an image’s merits as I do, it doesn’t actually make the choice you make then any less mysterious.

Can I play it or not?I welcome « accidents » and I think many other photographers do as well. If a person repeatedly makes something compelling by accident does that make it less artful? For me, random is a word we use to describe complex patterns that we don’t understand. As with Alex’s fire, it’s the best model that science can come up with, but not a real explanation. The same is probably true of anything else I can come up with to explain the inner process of making a photograph or of looking at one.

Today I am inclined to look at cameras in the same light as musical instruments and photographers as people who play them. Anyone can try to make music. It’s not how smart you are – or how expensive or sophisticated the instrument you have that matters. It’s what comes out the other end and whether it pleases you to play it or listen to it. Does it make you want to get up and dance; to cry; to stop up your ears and run from the room – or if you’re trying to play it, throw the damn thing out the window?

PROCESS AS ART I am trying in these short essays to share a little of how I think, work, make photographs and art. The reason they are called « Logs » is I have for many years spent a lot of time writing what I do each day as an aid to myself and my poor memory. […]

PROCESS AS ART

Rushing Water, Yosemite 2010 Mom Writing In Her Bookie 2014I am trying in these short essays to share a little of how I think, work, make photographs and art. The reason they are called « Logs » is I have for many years spent a lot of time writing what I do each day as an aid to myself and my poor memory. I found that much of what I do is so complicated that if I don’t make a record of it, at a minimum, it takes a long time to get myself back up to speed when my work gets interrupted. I called this writing a log for myself and so it seemed appropriate to call what I am doing here the same. I have other types of logs too – shot logs, print logs, and so on to keep track of other technicalities.

I wish I’d had the time to do the same for other big interests of mine such as economics and politics, but writing is a time consuming process for me. As it happens, my Mother has written nightly for at least 30 years for similar reasons and continues to do so today at the age of 91. She calls it writing in her « bookie », often recording no more than what we ate, who visited and so on. She more than anyone has encouraged me to focus on the process rather than on the result – the road rather than the destination.

I have only shared one of my actual logs with a few select people, mainly from my family, because they are sometimes highly personal and include my own struggles with doubt, fear and anxiety – which at times became a real factor in my work and so appropriate to note in the log. They also tend to be highly technical as one might expect given how I work, and so for the most part not that interesting to the average person. They are a record of what I am working on, not an all purpose diary. Still, they have also been a place where I can jot down ideas which I can also revisit later.

The log I wrote last summer as I struggled with rethinking and redesigning my current art project ran to about 500 pages. I can’t tell you how valuable that has been to me when I lose the thread or get stuck. It may take a couple days to reread it all, but it helps wonderfully to see the chain of thoughts and actions I took and usually leads to other entries as I reconsider what I have written. Most of the time I reread less – the last 20 pages for example, which suffices.

Computer Screenshot 2013 Microscope test using cell phone camera 2013I write these logs entirely for myself as part of the process of how I work and make art. I highly recommend the practice to anyone working creatively. Being able to review what you actually thought and did – even years later – is priceless. I see this « log » in the same light. I am in the first case doing it for myself, just as with my photographs. I look at it just as I do any other project I take on. It looks like something difficult and I ask myself, « I wonder if I can do that? »

After our cabinetmaking shop burned down, Sigi and I began working downtown San Francisco as finish carpenters through the local Carpenter’s Union. Much of the necessary work was not all that interesting or challenging to either of us, so we ended up with a saying: « The harder it is, the more we like it ». Now, years later, I have seen how much this attitude has shaped my life and work. I am a person who repeatedly and willfully bites off more than he can chew, which can cause me to bend right up to the breaking point at times. Sometimes I find myself ruefully remembering the expression and cursing.

Rushing Water 2, Yosemite 2010When I decided that it was finally time to make a website for myself, I had many long discussions with my close friend Adrien who had volunteered to do this for me. He convinced me that I had to share the process, the way I work, with others. He told me that I shouldn’t look at the technical aspects of what I do as secondary, but as true expressions of my art. He said, « David, you don’t realize it but the way you work is your art ». I guess it should be possible for me to accept this given what I learned from my Mother, but I’m still not sure that this is true. I know as an artist that process, the way you learn, think, feel, and approach things, often creates the conditions for something good to happen, but I feel that in the end, art has to stand on its own, like a foal finding its legs. Later, others will walk up and walk away with their own ideas of what they saw.

ON PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE REAL I have spent a lot of time thinking over the years about how people see things differently and inhabit their own personal realities, as well as how much of reality a photograph is capable of capturing. I tried to write about this several times but always grew frustrated in the […]

ON PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE REAL

Ice on Lake Erie by Robert SchnellbacherI have spent a lot of time thinking over the years about how people see things differently and inhabit their own personal realities, as well as how much of reality a photograph is capable of capturing. I tried to write about this several times but always grew frustrated in the attempt. It seemed the more I wrote, the more meaning drained away from what I thought I had to say. Here is something I wrote in 1991 – just about all I can quote from one of those documents without cringing:

Far from being simply an objective representation, a photograph is a merging of subjective realities, of the artist, subject and viewer… as Picasso wrote (of a painting) in 1935, « …when it is finished, it still goes on changing, according to the state of mind of whoever is looking at it. A picture lives a life like a living creature… This is natural enough, as the picture lives only through the man who is looking at it. »

Part of the reason that approach never worked for me, is it is clearly a little absurd to try to say anything worthwhile when the topic is « reality ». Unfortunately, that is where I have to go because of the association of photography with the real and how my experimental approach led me to think otherwise. I think the only way that I can navigate through this ridiculous task is to stay as much as possible focused on photography, how to take good photographs, and the creative process. I have to say that this is also ridiculous, but not quite as bad.

Pink Floyd, The Division Bell (1994) coverAs I was thinking about this all again last night, wondering if I could actually write anything, a song began playing in the café I was hanging out at. An album cover showed on the monitor on the wall from Pink Floyd – the Division Bell.

At the time I was thinking about the inadequacy of the terms conscious and unconscious and of how important sleep and dreaming are to what we call our « self ». Artists rely on this other part of our consciousness a lot – and not only during sleep. This type of thinking is less about following a chain of logic to its conclusion and more about waiting patiently for the idea to come to you. You do this in part by suspending the « conscious » thought process, at least in part – you just stop trying to force your own ideas on the problem. I saw the album cover as a metaphor for the opposition, the duality of consciousness, because one can also look at the image and see one face. The beauty of the image is that one can project upon it any duality one chooses.

It should come as no shock that I rely heavily on the former way of thinking most of the time. It is what makes both craft and science possible, but when I’m stuck, I turn to the other method to see me through. Here, almost anything you say gets squishy, but I’ll use the common phrase. « Something told me » to start with Bob’s photo of ice on Lake Erie.

My sister and Bob in HawaiiThe ice pieces in the picture above remind me of how our attitudes gradually harden and separate from others, just as with ice, as we become « ourselves », but that’s not the reason I think I picked it. I think there’s no better way to talk about photography and the real, than to talk about Bob, my brother in law, who took the picture.

Robert was an extraordinary person, both in his gifts and modesty. Those of us in the family knew about his incredible photographic memory, able to recall events from the distant past – menus, what everyone had eaten, who was there, pictures that hung on the wall – but he kept this mostly hidden, almost as if ashamed. What I learned from my sister after his death was he also had an equally powerful kinesthetic memory. Simply touching an old ticket stub or a photo from the past brought forth a torrent of memories that at times overwhelmed him for hours, unable to move or speak as he vividly re-experienced the past. My sister knew this and tried to protect him from it by hiding things she knew could trigger such an episode in red folders, so he knew that if he ventured there he would at least be prepared.

His memory gifts though went even beyond this. I remember taking the family up a hill above my home in San Francisco during a visit, now called Corona Heights. At one point he wandered off and I later learned that he had a flood of memories from the place although he had never visited it. He said it had been used for ceremonies by Native Americans in the distant past – he could see and hear them, incredible as it may seem. After his death, my sister told me that once on a visit to Arles in France, he told her that they were together there in Roman times, as he insisted they were in other specific times and places. He was a legionnaire and said the quarters were just around the corner. He led her directly there and sure enough there was a plaque describing it. Bear in mind, Bob was not prone to exaggeration nor did he seem in any way a mystic or religious. The only way he was unrealistic was in his underestimation of his own abilities – he disparaged them constantly.

Untitled by Robert SchnellbacherHe was a perfectionist, able to teach himself almost anything, a high level competitive pistol shooter and a life long photographer. Always hard to tell with him because of his modesty, but I got the feeling that he found photography frustrating. We of course had conversations about this, but these would often end with him saying, as if raising an objection to my sanguine comments, « Ah but what to shoot… »?

The way I looked at it, if anyone understood how different reality is from what the photos he took could represent, it was him. I even wondered if photography was like a language that lacked the words necessary to even begin expressing what he saw and felt. In retrospect I think this was both unfair to him and to photography as an art form. I think it’s more likely he approached photography a bit like he did target shooting, which required preparation, training, nerves of steel and taking the shot, and he never confused shooting with life. The conundrum for him was, with photography there is no set target. In this context, it didn’t matter how few techniques he had to work with. Straight black and white photography was an entirely adequate field in which to test himself.

My sister tells me his way of working evolved once he started shooting digitally, partly because there was no longer a cost factor and he shot a lot more abstractions and reflections. He also tried to show what he was feeling when looking at something rather than simply recording it. I am looking at some of them now, since I copied his archive on my last visit, and I am at a loss on what to pick – so many are beautiful while being classically photographic.

ARTISTIC FIRSTS Here is a photo that I was overjoyed to find while digitizing family photos last year. It shows me perhaps at the age of 13, proudly in front of what I considered my first painting – the first one I did on my own initiative and valued. I used an old roll up […]

ARTISTIC FIRSTS

Me in early 70’s with first paintingHere is a photo that I was overjoyed to find while digitizing family photos last year. It shows me perhaps at the age of 13, proudly in front of what I considered my first painting – the first one I did on my own initiative and valued. I used an old roll up window blind as the canvas. I gave it to my sister as a Christmas present but it was lost and I despaired that I couldn’t remember it exactly. I copied the design from a National Geographic. I already had a favorite artist – Picasso. A couple years later it would become Vincent Van Gogh, who I love to this day.

A shot of my nephew for a high school photo essay which I found recently – one of my first photos ever. 1974Another picture I found shows my first « photographic project ». I have written elsewhere of how I never used cameras before taking up photography in 1989, but this is an exception. I tried a while to work for the high school newspaper and decided to make a humorous photo essay for it, borrowed a camera and shot my nephew wandering the halls as if it was his first day at school. This photo was evidently not processed properly so it has turned into something else with the decades. Strangely, it is the sort of thing I might do today if I could. I love « accidents » like this. It’s as if life is showing you how to make art, to see the beauty in the process and the flaws, in time itself.

My first self-printed photo? Angel Island 1987 or 1988Another, sadly not well reproduced here, can be said to be my first self printed photo. I was studying movie making at City College San Francisco. My girlfriend was meanwhile studying photography. She told me one of her classes was taking a field trip to Angel Island and that the best photo would get a prize. Angel Island was formerly a military base in the SF bay, which had abandoned barracks, all without doors, windows or staircases, in the midst of a huge eucalyptus grove. She inquired and I was allowed to come along and participate, even though I only could shoot using my Super-8 film camera. The topics of the competition were doors, windows and photographers taking pictures. It may be difficult to see, but this is a picture of someone using a camera on a tripod to take a picture of one of the barracks windows.

I looked through the frames I shot and picked a couple to try to print. This meant making an internegative on 35mm black and white photographic film myself, something I’d never done. I used the enlarger I’d bought for my friend to do this and then to print the photo I submitted, again my first. At that time I was using a manual processing tank to develop my movie film. It was quite easy to get agitation problems and end up with wild processing flaws, which I naturally liked. I picked one that seemed most ethereal as well as most messed up chemically speaking.

I learned later that my photo was selected for the final round in the competition, even though I wasn’t taking a photo class. I was told I nearly won but it provoked an argument between the teachers who formed the jury. I never got it back unfortunately – apparently it was lost. The copy I show here was a poorer quality work print copied by my sister using her cell phone for me. I still have the film though so perhaps one day I will reprint it. I remember it looking fabulous with rich blacks and hazy, smoky developing flaws.

ON PERFECTION AND FLAWS IN ART AND CRAFT It is in my nature to be a perfectionist. Ironically, that has only made me more aware of the flaws in my work and in my life. What I learned from the craft of cabinetmaking is flaws are at times unavoidable, so the more important thing is […]

ON PERFECTION AND FLAWS IN ART AND CRAFT

In search of the Perfect Pizza.It is in my nature to be a perfectionist. Ironically, that has only made me more aware of the flaws in my work and in my life. What I learned from the craft of cabinetmaking is flaws are at times unavoidable, so the more important thing is to know how to deal with them. If you can correct your mistake, I was taught there is really no lasting fault – therefore always pay attention and avoid those you can’t correct. However, so much depends on the tools with which you have to work. If I’d had a truly well set up shop with all the grand machines that help one quickly get the best result possible, the scale would have been a bit different than when using what I had at my disposal – constrained to non-professional, even defective tools, often having to do things by hand. The craft I learned was how to nonetheless still get a good result in spite of these deficiencies.

Over time I came to see that this was less of a handicap than it seemed. When one does something by hand, for example cutting dovetails using a simple saw, chisel and mallet, the result is governed by your hand – every momentary angle you hold the saw, how deep you happen to scribe your chisel line, even your mood at the time, since if you are impatient you can easily slip here or there. A professional can see these sometimes tiny flaws, which is the basis for any craft. Sometimes seeing them actually makes you recognize that it was handmade.

However, something very subtle may emerge out of doing something by hand that takes you out of the craft scale of having done something well or not. There is added a personal, almost organic element to what might otherwise be looked at as a thing, lifeless in itself. Much of the cabinetmaking I have done is not fancy, high end stuff, but practical, functional things needed using the cheapest materials possible. Still, even with work like that, I’ve found that people can often sense this personal character in a table, tiled floor, and so on, even if they have no conception of the craft in constructing it. They see it as having a much higher quality than I do. Something else shines through in spite of the flaws, or on some level, because of them.

The impossibility of perfectionAs a child and even later in years, when I was frustrated at my limitations, my Mother always said to me, « only God can make something perfect ». One idea behind this is that human life and our efforts are always flawed, so we have to simply do our best and accept that the result will never be what we hoped for. Another is that there is another kind of perfection immanent in life which includes the flaws we see. Perhaps that is one way to define art – it’s a vehicle that allows us to see this, appreciate it, and laugh at our foolish notions of perfection.

I’ve spent much of my career as a carpenter correcting the flaws of others. There is the usual catalog of peeling paint, ground in grime, leaking pipes and so on, but I took an enjoyment in this and not only in my work as a carpenter. I’ve repaired so many things I’ve been handed by others or come across in the street and enjoyed repairing them all. For me it’s a sort of inner directive, and of course, it is also satisfying to see my efforts result in a tangible improvement in my life or someone else’s.

One day I was sitting in my room and glanced at a stain in the wall puzzling over it. Suddenly I was transported back a few years to a painful breakup. I was so upset I’d thrown a coffee cup against my wall and watched the liquid drip to the floor. Coming back to the present, I got up and looked around my apartment and could remember several other things that had happened there just by looking at the flaws around me – the time a friend dragged a trunk across the floor, deeply gouging it, or a bump in the wall created carrying my film recorder up the stairs. I began to see flaws as the traces we leave behind in our passing and saw them literally everywhere. I wanted to make a movie out of it at one time, that showed how every nick and scratch, no matter how old, had a story to tell. Our world is densely layered with these traces and stories. It is the ground we walk on.

Tunnel StaircaseIn my photography the flaws are even more apparent to me than in my efforts as a carpenter. Although I approach my work in as professional manner as possible, the fact is I’m always trying to learn and do too many different things, usually without a guide. As most do, I learned in school the exacting craft standards of what makes a good exposure, negative or print, and tried to achieve this, but I’ve seen that everything I do is in a way handmade. Each print is different, in a way is born as an individual, rather than stamped out by a perfect reproduction process. I felt instinctively that this was not a defect but a voice beckoning me to follow.

When I did my first 16×20 finished prints in 1989, I made many tests until I came up with a photo paper and chemical process combination that I liked. I ordered a huge amount of the paper, perhaps 25 boxes of 25 sheets each, at great expense but excited at the prospect of printing my images perfectly. When the heavy box was delivered to my door, before I could sign for it, the delivery man hefted the big box and dropped it on its corner. I signed, thinking nothing of it and only weeks later began using them to print. At that point I discovered almost every sheet had its emulsion cracked at one corner, In other words, they were all flawed – some would say ruined – but it was too late to do anything about it. I printed with them anyway, with my Mother’s words ringing in my ears.

I have taken an approach to photography that might seem to a lot of people like it throws the photographic craft right out the window. How can one think you can make a good photo when you don’t even use a real lens? I guess this is where I could say that art truly meets craft, but walks by unconcerned. I felt that one’s eyes are the true camera and so how you see, the sentiments you express, the personal, will all be more important in the end in creating an image than the more craft based notions of proper equipment and best practices. It doesn’t mean I don’t value craft – more the opposite – but craft can only take you so far. Flaws too remain something I combat in my work and life, but I have come to see how much they form the beautiful fabric of our existence.

Me, having made an imperfect pizza, that was nonetheless enjoyed by all.I am quite sure that there are people – smarter, more knowledgeable, skillful or talented than me – who could have done any of the things I’ve done, only much better technically. For me this has always been a given because I understand the nature of mastering a craft. Even for something as simple as carpentry it takes a lifetime, until the body and mind are finely tuned and what you do naturally turns out well. Being who I am, I am all in favor of striving for perfection, but in most things I’m afraid it’s a mirage, and in the end it’s not the measure to rely on, neither for art nor life.

When you look at the sea, is there such a thing as a perfect wave – or can you find a perfect person, plant or tiny flea? Everywhere I look I see individual beings, beautiful in their individuality and more beautiful still when considered together, as a whole. My German cabinetmaking partner wrote a motto on our first business card: Gott Gruß das Handwerk. Although you can translate this in a few ways, I like, « God likes work done by hand » – and I would add, with flaws and all.

PRINT SCANNING USING A VACUUM TABLE (TECHNICAL) Instead I went ahead with shooting my prints. The main advantage was I had done all the work necessary to print them well so I could focus my attention on getting a good scan. Early on I made a decision that added a fairly large sub-project to the […]

PRINT SCANNING USING A VACUUM TABLE (TECHNICAL)

Vacuum table carcass 2017Instead I went ahead with shooting my prints. The main advantage was I had done all the work necessary to print them well so I could focus my attention on getting a good scan. Early on I made a decision that added a fairly large sub-project to the mix. The problem I foresaw was getting the prints flat. I had an easel/setup I’d built earlier for copy work but the B & W prints were curled worse than the color ones and I noticed reflections and bubbles with both – sometimes it looked more like waves on the ocean than a flat surface – and doubted I’d get the quality I was after that way. Why buy a high end camera and shoot that?

I decided to build a vacuum table to hold the prints perfectly flat when shooting them. I spent some time trawling the internet and found sources that helped me design my own. There are industrial uses for vacuum tables even for cabinetmaking so I read about them too and ended up using some ideas from them as well – principally in creating chambers that could be shut off when shooting smaller prints as well as being able to regulate the pressure going to the individual chambers as needed. Here is the carcass I built to start with, using scraps I had on hand as well as castoff pieces I’d used as backing when drilling holes…

Vacuum table base with stands added and completed manifold with vacuum feed pipes 2017 Vacuum Table in horizontal position 2017Here it is later on in the process, along with the manifold with the valves and pipes to feed the table from my old large Sears shop-vac:

And another shot of it completed. I repurposed a stand I’d created years earlier which I used to add paint layers/exposures when I was doing multiple exposures. Here I incorporated an idea I got from a fine article describing how to make a vacuum table for art copying, by making the table tiltable. In this photo it shows the table locked in a horizontal position. You can also see the other end of the manifold that connected it to the vacuum cleaner which I kept in another room, as far away as I could get it due to the noise.

Working with the vacuum table was a dream. I was able to use it to quickly shoot not only my prints, some as large as 30×40″, but also family photos that I decided to digitize, as well as all sorts of documents. I also created an apparatus to hold the camera that could slide on stainless steel rails for the stitching of multiple photos which you can see in the following image of the table in action. Although I didn’t stitch any truly high resolution photos for this site, I found using the rails helpful in aligning the camera as well as in making small adjustments to center the photo. The monitor I attached to the camera was a very defective one that I managed to calibrate into a useable range for focusing. It actually looks worse than it was in the following photo, more a function of a mismatch between the color of the lights and camera, than its poor quality. I have of necessity used lots of very defective equipment over the years. For lots of tasks, it really didn’t matter, though I did save lots of money doing so.

My circa mid 80s Sears shop-vac showing spill valves 2017 Vacuum Table in action – gray areas you see are for chambers that were shut off for this size – 2017You may be able to just make out the router speed controller on the floor to the right of and below the monitor that I used to regulate the voltage to the shop-vac. It allowed me to further fine tune the suction so that I could get the prints flat but eliminate the dimpling caused by too strong of a pressure as well as reduce the noise substantially.

Even more important though was adding spill valves to the shop-vac itself. When I was building the table I was unsure if I would be able to get enough pressure and so I sealed everything as best I could, using glue, bondo, caulking, paint and rubber gaskets. The problem turned out to be the opposite – the shop vac and vacuum table were too powerful for delicate artwork. It could in fact be used for industrial purposes, at least by me. Here is a shot of my shop-vac about 30′ away in another room with my spill valves. You can see the one closest to the intake is wide open – spilling half the vacuum force – and the other is a little less than half open – spilling another 10% or so of the force. This got the suction into a useable range that I could fine tune with the voltage controller.

Using plastic wrap to seal holes for mural prints 2017For those interested in doing something like this, I would like to point out the importance of covering all the holes that are creating suction with mats, for standard sized prints, or some other arrangement, such as plastic film packing wrap which I used to quickly seal rows of holes when shooting large prints. Any vacuum table whistles and howls terribly. I found it impossible to think with the noise and I knew I had to work days with it. After covering unused holes, I found that the noise dropped down to a whisper, almost totally quiet. It is also important to move the shop-vac far away and sound proof any doors leading to it as it too is extremely loud. Between these two strategies I dropped the sound level from around 100 decibels to a comfortable 40 to 50. It would have even been less but the basement I did this in has central heating ducts that connect the two rooms, so a very little sound from the shop-vac travelled through them. Nevertheless I could listen to quiet jazz as I used the table. In the end, I found for prints that were 16×20 and below, it was quicker to keep the table vertical and use plastic corners to hold and align the print before adding the mat mask.

Another hint has to do with the drilling of the holes for the top or tops, which is important because there are thousands of holes to drill. I had two tops, one made of two peg boards that I contact glued together and an outer one made of acrylic with smaller holes. In retrospect I should have scrupulously followed the Wilhelm Imaging article as it would have saved a lot of time as well as wear and tear on my arm. Using pegboards to save time was a bad decision. The ones I was able to purchase were not uniform and I ended up also adding another set of holes between them and for the perimeter of my most used size (16×20″). It is far better to start with a flat sheet of mdf and drill all the holes as they recommend, unless of course you have access to a CNC to do it all for you. Happily, in spite of the mistakes I made building it, it turned out fine.

Vacuum Table top showing acrylic surface 2017 Vacuum table in horizontal position showing front of manifold 2017My vacuum table is heavy and can barely be lifted by one person, which I had to do to mount it in the stand. If I had to do it again I would probably try wherever possible to use lighter materials and build the chambers less deep. That said, using my cabinetmaking skills, I was able to build it absolutely flat, which was partly possible due to the gauge of the materials. Once in place, if you have the space for it which I did, there is no need to move it and it was wonderful to work with – it looks and feels like a professional piece of equipment. As they say though, the proof is in the pudding. More important for me was I was very happy with the scans I got from the process, of which the vacuum table was just one part. For those interested in dimensions, the table is about 48x32x5″ not counting the manifold or legs.

Interestingly to me, even after using such fine equipment to shoot my prints, I still heard the echoes of their strange origins in my wildly varying negatives. I found they still had to be dealt with individually rather than applying blanket settings to the files. This however was pretty subtle, more a question of tweaking the color balance through the camera’s raw file conversion settings, and I didn’t agonize over it. On the contrary, I tuned the final image settings quickly by eye, by comparing my calibrated monitor image to the print I taped to the vacuum table as reference. Below is an example of the notes I took as I went through this final process.

Print scan processing notes sample 2017NEGATIVE SCANNING USING A DIGITAL CAMERA (TECHNICAL) Since all my photos have been printed analog from negatives using an enlarger, you may wonder how I digitized them for this website. I will try to give a short explanation for those that are interested in the technicalities. I think it will also give some insight into […]

NEGATIVE SCANNING USING A DIGITAL CAMERA (TECHNICAL)

Since all my photos have been printed analog from negatives using an enlarger, you may wonder how I digitized them for this website. I will try to give a short explanation for those that are interested in the technicalities. I think it will also give some insight into how I work and approach such « projects », which is part of the purpose of this Log.

I’ve researched scanning a lot over the years. I looked several times into drum scanning but the only way to do it economically would be to buy one and I knew from my experience with the LVT film recorder that using old equipment can be difficult and very time consuming to master. From what I read, drum scanning is much more an art than a science, so getting it running is not the end of it. These also tend to be huge and heavy machines that are impractical to find place for or worse, to move, so I looked into other options. At one point a few years ago I managed to purchase a high end flatbed scanner from a company going bankrupt after the great financial crisis of 2008. Unfortunately, the sale was cancelled before they shipped it when the company realized that they no longer owned the scanner and had the rights to sell it. That particular fox got away.

The upshot was when I decided to finally make a website, I decided that the best and most economical way to digitize my photo artwork was to use a digital camera rather than a scanner. I wanted to end up with digital files that were good enough and of high enough resolution to print digitally in large format, since printing analog had become all but impossible after leaving my home in San Francisco. In December of 2016 I purchased my first digital camera specifically to do this. I figured I might get quality comparable to a higher end scanner and after it was done end up with a great camera as a bonus. I bought a Sony mirrorless camera (A7rii) because it had a relatively high resolution as well as being smaller than other professional cameras, which I doubted I would enjoy carting around. I also got a high quality but affordable macro lens that could resolve nearly all of the camera’s 42mp. These turned out to be great decisions as I saved tens of thousands of dollars it would have cost having them scanned professionally and I could control the process myself which I always want to do.

Shot of 4 of my cross processed negs on my light table showing color/exp variation – all the same film typeIn an intense couple months, I worked out ways to shoot both negatives and prints, including working out ways to create even higher resolution files by shooting many overlapping images that I could stitch together, but I determined that shooting the prints was the faster and better path forward for me. I found that the color of the light I used to illuminate the negatives was extremely important in getting a good negative scan. For most photographers, this might not be such a hurdle to jump since once you arrive at a good result for one negative type, you can more or less do your whole archive using the same settings. However, my negatives vary tremendously because of the experimental chemical and optical processes I used. Here are four random negatives I pulled out and put on the light table to examine when I was doing the scanning – all nominally the same film type – but with the bleaching and wild exposure differences they don’t scan the same. You may be able to tell from the photo the base emulsions are not the same color.

I found that of the hundreds of negatives I would have to scan, I would have to treat almost each one as if it was shot on a separate film type. On top of that, even after doing my best with a few, I saw that converting the negative digital file to a positive was very similar to printing a negative, which as I have said elsewhere was challenging with many of my negatives. The negative or positive files would have to be digitally burned and dodged too, sometimes extensively. There would be many artistic and technical decisions to make and these would vary for each negative. It would have taken forever.

Negative Scanning setup close up 2017Nevertheless it might be interesting for some to see the negative scanning setup I improvised. I used a stereo microscope stand I’d bought years earlier on eBay to hold the camera as it is built very robustly and allowed me to move the camera in registration to the film plane if I wanted to stitch multiple shots together. The table was an old

My improvised negative scanning setup 2017one I’d built for my darkroom that I cut an opening in for the light source, which was an old color enlarger head I’d also gotten years before. Using a color enlarger head is a great idea as it allows you to vary and precisely set the color balance of the light source. I got a piece of optical glass for the top layer where the negative was placed. It had just enough coverage for a 4×5. You can also see here a shot of the whole setup in use which shows how I was struggling with different color balances for a final scan.

What caused me to abandon doing it was time. There simply wasn’t enough to do my portfolio properly much less all the other images I wanted to scan. I would like to revisit negative scanning in future, especially perhaps for negatives that I decided were unprintable earlier, but for my negatives I found the process impractical given the time I had available.

LOTTA’S DREAM I met Lotta, like so many other people who modeled for me, in the Café La Boheme in San Francisco. She was a painter from Sweden and readily agreed to model nude. I was ecstatic at the results as my pictures of her were some of the first really good nudes I shot […]

LOTTA’S DREAM

Lotta’s Dream 1989 LottaDbl 1989I met Lotta, like so many other people who modeled for me, in the Café La Boheme in San Francisco. She was a painter from Sweden and readily agreed to model nude.

I was ecstatic at the results as my pictures of her were some of the first really good nudes I shot using my wineglass lenses. In the shot Lotta’s Dream, I had her lie down on one of my tables and draped some cloth and taped up a bit of Mylar behind her head. I had the weird thought that the Mylar might look like flames. How wrong I was. As I saw then and found out much more later, Mylar would speak in its own language.

To the right’s another shot I took of her the same day. This one has puzzled me since I first printed it. I’ve always suspected that the strange « double » face of Lotta was actually a reflection of me behind the camera caught by the unshielded wineglass element hanging in the air in front of the camera. I think this may have happened more than once. This is another strange aspect of this type of photography – it’s as if what happened in the room when I shot her is the subject, not simply her.

LottasDrawingSnusMumrick 1989 Tarot card I found in San Francisco in early 80sWithout intending to, I shot them all with her face in focus and pretty much undistorted, but each looked beautiful to me. Later, when I knew her better, she told me that I reminded her of the Snus Mumrick. I didn’t know what this mythical character was so she drew a picture of one for me. Happily I still have it and can share it with you.

She also told me I could easily become a painter if I wanted to – I just had to pick up a brush and start. I doubted this but the fact that she insisted helped my confidence because I trusted her honesty and opinion.

Her drawing reminded me of something I had sitting on my desk. It was a tarot card I found on the street, well before I met her. Why did I pick it up? I think it is actually the same reason I take one picture and not another. It seemed as if the wind had blown it there for me to find.

LottasDrawingwCamera 1989 Holbein postcardThe same day she made another drawing of me with my camera, all of course from her imagination. I love that one also because it shows me in my Renaissance hat.

While in Vienna in 1986, I made a few dozen Renaissance hats and walked around the bars and cafes there calling out « Hats for sale » in German. I sold some but gave most away – the story of my life. I kept a couple for myself and wore one from time to time in San Francisco.

Self made seal for Renaissance hats 1986I made the hats on a whim. I’d gone through the museums in Vienna and was impressed by the older paintings. I bought a postcard of a one I liked by Hans Holbein. I thought the hats they wore then were cool but no one made them so I decided to do it myself. I liked the postcard so much I had it propped up on my desk for decades.

Finally, to really end this story, is the seal I put into each of the Renaissance hats I made. I made a stamp with the motto « New Renaissance » and glued in the cloth you see in the photo I have here. Although I did this partly for personal reasons, in my idealism I also wanted to believe that something like that was possible in our age.

Despite all I have learned about the ills of this world, today I still think it is possible to give birth to a New Renaissance.

SIGI – THE PROPHET One day, not so long after moving to San Francisco in 1981, I wandered into a cafe and sat down at a couch next to a middle aged man exactly twice my age. I was carrying carpenter’s tools with me in a bag, which he noticed, so with little ado we […]

SIGI – THE PROPHET

(from left to right Sigi and me – on a break 1983?) Gallery House*One day, not so long after moving to San Francisco in 1981, I wandered into a cafe and sat down at a couch next to a middle aged man exactly twice my age. I was carrying carpenter’s tools with me in a bag, which he noticed, so with little ado we began to talk. Within a short time we had a workshop together and I began to really learn my craft, because he was above all a fine craftsman, schooled in the traditional German way which did not exist in America. I knew next to nothing really but I learned it from scratch from him and took to it like a fish to water.

However, Sigi Krauss was and is far more than that because of his former life in the middle of the art scene during the swinging 60s in London. He had a couple very avant-garde galleries that showed cutting edge, political and provocative art for several years until each in turn was shut down, mainly because of the political content he was showing. One was the Sigi Krauss Gallery and the other, right, was Gallery House, closed by the West German Government.

He was also married to a very talented artist who was the daughter of a famous artist, Jean Tinguely, and friends with many other artists – some also very famous – such as Sigmar Polke, Jeog Immendorf and Katerina Siverding. So in between discussions of politics and craft, I heard story after story of the rarified world of Art: the commerce, rebellions, the crazy stuff and people he was involved with, and along the way the zeitgeist of what it was to be an artist. He was also a high end framer of art sometimes doing so for the largest museums – think Rembrandt – and very obviously to me, an artist himself though he would never say so himself. Very often our commercial work was halted while we made stretcher frames for one painter or another gratis.

We were never successful in money terms as cabinetmakers. This was probably an impossibility given who we were. Both of us were idealistic and obsessed with quality, while I had a complete lack of any experience in business, of which I was the nominal head at 23 years of age.

I was feeling the pressure of slipping deadlines, lack of funds to buy materials and of other work commitments we had made but could not fulfill due to the pace of work done well, mostly at that point by him. But, despite all this, Sigi and I continued taking his dog Sara for walks through the Mission District or to the ocean, stopped work to drink tea or make frames for an artist, and talked. I so felt the pressure that I began pressing him to allow us to make some dubious shortcut in the way we were working. He suddenly got angry and frustrated which was rare. I can still see his reaction as if it were yesterday. He didn’t shout or berate me. He just stopped what he was doing, held out his hands, almost shaking, palms up and stared into them and said, « These hands won’t do bad work. » The argument was over, and for me in a way settled for the rest of my life.

Sigi3 – The Prophet 1989Sigi has to be one of the most interesting people I’ve ever met in my life – skilled, sophisticated and a natural story teller – and he had a big influence on me. I of course did make a few portraits of him when I began taking photos with the wineglass lenses. I think I did four shots of him in all while he was sitting in a café drinking tea. One especially pleased me as it reminded me of my conception of what an Old Testament prophet would look like, which seemed to ring true in so many ways to me.

Below it is another I’ve made into a kind of diptych. The left was a print that had a severe developing flaw that I loved, so while writing this I’ve flipped and combined it with the « normal » one. Perhaps one day I will find time to print the two together like this.

SigiRorBlot 1989/2018

* Visit the website for Gallery House photo here.